Beau Brummell: The man who invented style

By Robin Dutt

In a world suffused with fashion, “best-dressed” lists and the electric vulgarity of celebrity (whether A or Z), it is often the case that real style is forgotten – if recognised at all. So can style truly be created? Of course the answer – from Savile Row to Jermyn Street – is a resounding yes.

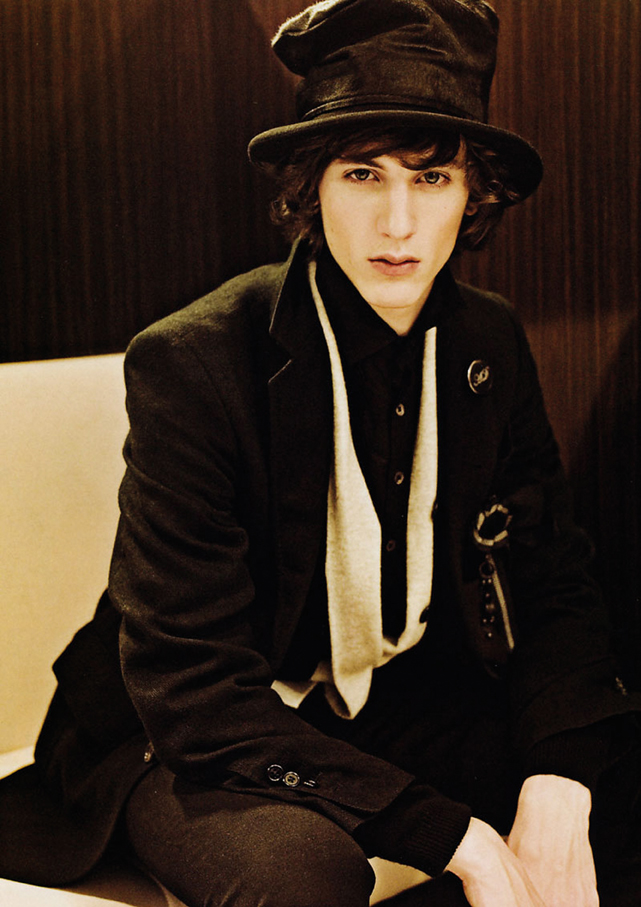

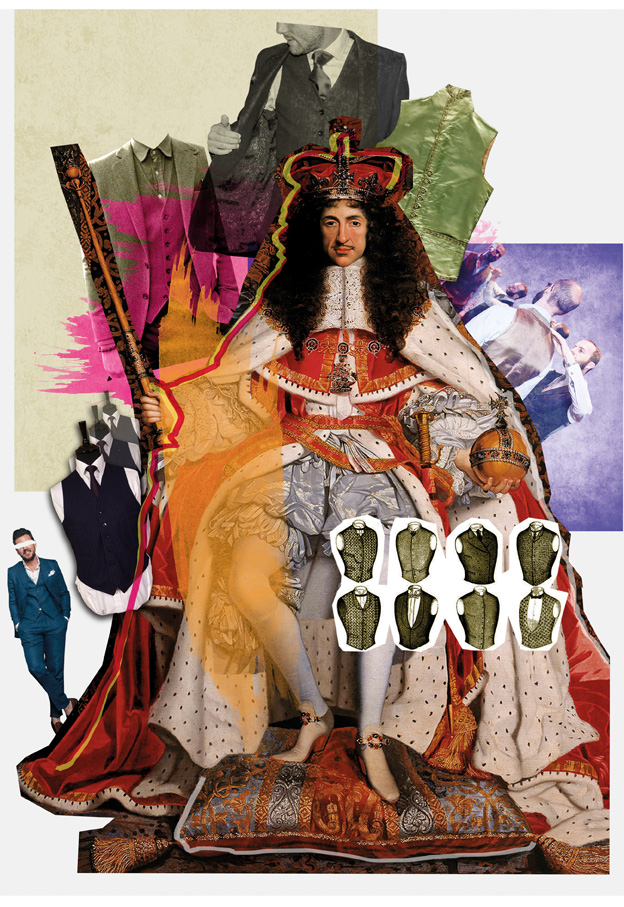

George Bryan Brummell – known to all as Beau – set an almost impossible standard for simple elegance in Regency England – a man who cheerfully eschewed the sugary flummery of satins and silks and patterns for streamlined minimalism. A style that is always difficult to do well. A dandy in his own time, Brummell trumped the fops, macaroni, pretty gentlemen and lions – overdressed, over preened, overdone. Few designers today can truly understand the purity of this stance, but some like Ann Demeulemeester, Rei Kawakubo and Carlo Brandelli certainly do. Tailors, however, are automatically hard-wired into his beliefs since they are the basis of fine cut in the first place. Cut, colour, cloth – the sartorial man’s 3 Rs – are the pillars of this time-honoured temple. Brummell’s was an elegance which immediately attracted the Prince Regent, and for a while these two made a fashionable couple at race meetings and banquets.

By so doing, Brummell was catapulted onto the social scene and beyond to the extent that when having a fitting for a suit, tailors would stuff the pockets with money in the hope of being introduced to the future king. There is also a story that when a tailor was asked by a customer which cloth to choose the immediate answer was Brummell’s choice, not the Prince Regent’s.

Born in 1778, 18 years into the reign of George III, Brummell used his charm, wit and waspish tongue to great effect, believing wholeheartedly in himself. The confidence in the way he dressed – sharp and even aloof – finds an echo in many of his purported statements, bon mots and repartee. When asked by an ardent lady who was eager to meet him to come to her chambers and take tea, the reply was a delicious put-down. “Madam, you take medicine, you take a walk, you take a liberty, but you drink tea.” On another occasion, accounting for his lack of a female companion, he said: “What could I do… when I saw Lady May eat cabbage?” This coming from the man who once confessed to have only eaten a single pea. High, meaty Regency standards indeed. Looking at the menus of the celebrated Careme, for example, vegetables only ever have walk-on parts.

Brummell was iconic on the Regency scene, hugely instrumental and influential without being of birth, but possessing, for a short time at least, a legacy from his father, some £25,000 or so which today would amount to a spending power of some £1.5 million.

There are few surviving images of Brummell today and most are well known. Despite not being classically good looking and having once had his nose broken by a horse’s kick, they all show a definite haughtiness, an air of extreme grace and that famous, intricate cravat – some 12 inches wide. The only image which is close to caricature is one of the last, depicting him as a threadbare pauper, hunched back, tattered, old-fashioned clothes and bearing a walking cane whose top was a carved head of his one-time friend, Prince George.

Claiming that one needed at least five hours to get dressed and not getting up too early in the morning (for it to be thoroughly aired), Brummell had many quirks. Gentleman would queue outside his house in Mayfair’s Chesterfield Street to watch him getting ready for a day’s pleasure at his club, the gaming tables or commissioning another snuff box. Today there is the blue plaque to remind us.

Brummell had his boots blacked till they shone like light itself and even demanded the soles to be ebonized. According to sartorial legend, he finished off the polishing process with the tops lavished with the mousse of the finest champagne – something I witnessed Olga Berluti of the shoe supremo, Berluti, perform as almost a sacred act – in tiny circular motions. Brummell changed his shirt three times a day and once had the confidence to say to a gentleman who asked his opinion about a newly commissioned coat: “D’ye call that thing a coat?”

Perhaps, apart from the sparseness of the cut of his clothes and the practical duo chrome simplicity – one garment informing other – Brummell is credited with having invented the narrow ankle trouser. This was much like a vintage ski pant with straps under the foot to keep them taut.

He ignored jewellery, but invested in “plenty of country washing”, certainly not of his time as people in general regarded bathing as dangerous. Many women slept with cats to deter the mice which nested in their wigs which they did not remove at night nor have washed. Brummell’s obsessive cleanliness even extended to removing with tweezers every last facial hair daily to give the smoothest, marble-white complexion possible.

Of course favour and fortune could not last, especially combined with an addiction for gambling and an over confidence where even Prince George was concerned. There are two stories that seem to signal Brummell’s downfall. Once, when dining with the Prince, he said tartly, “ring the bell, George.” Then whilst out with a companion, he met Prince George strolling with a friend. “Who’s your fat friend?” was enough to destroy Brummell.

Brummell fled to France, avoiding both his creditors and debtors’ prison. Meanwhile his possessions were ignominiously sold at auction accompanied by an advertisement – once belonging to “a man of fashion, now gone to the continent”.

He ended his days in an asylum, tended by kind nuns, raving and doubly incontinent. A humiliating ending for the man that defined the path of modern and contemporary masculine dress. His importance though is too great to let him be forgotten. He remains the gold standard when it comes to male attire.

By Robin Dutt In a world suffused with

![SR spring cover[1]](http://savilerow-style.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/SR-spring-cover1-150x150.jpg)