Game, Set & Match

Trevor Pickett looks back over his 30 years at the heart of Savile Row

Trevor, you set up Pickett back in 1988. What did you hope to achieve at the start?

It was exciting for me that I suddenly owned my own shop in Burlington Arcade, which was quite an achievement for someone aged 25 who left school at 16 and I suppose I felt rather pleased with myself. I’ve never been desperately ambitious in the sense that some people have a much bigger focus on global domination – ‘money, money, money’ – that can compromise on integrity. I do like a lifestyle. I was excited about what I had, then I opened the Georgia von Etzdorf’s store on Sloane Street store three months later. The things I do for work are passions, and GVE was a passion, I felt it gave me access into the arts.

There were fewer challenges in the early days. It’s become more difficult now. The challenge nowadays is the competition; it has gone from being small independent leather goods shops, of which there were quite a few, to every shop brand or store now selling leather goods. With the coming of the internet, we can’t sell products which you can buy just as easily online, so ours must be wonderfully individual. We make everything in our own leather, in our own styles, with our own linings, with our widgets and fittings. It’s much more of a challenge but it’s exciting. It’s nice to go down the street and know that the product is definitely yours because of its unique features.

How important is it for you to promote the British leather industry?

We’ve built our reputation on selling British-made leather goods so, where we can, we always buy British. It’s become a diminished market and we tend to be buying from a smaller source but a higher quality because only the best survive. I don’t think we’ve lost many manufacturers at the top end while the middle and lower markets were hit more by the imported product. There is something special about English crafted leather, an honest rawness in the traditional luggage and briefcase.

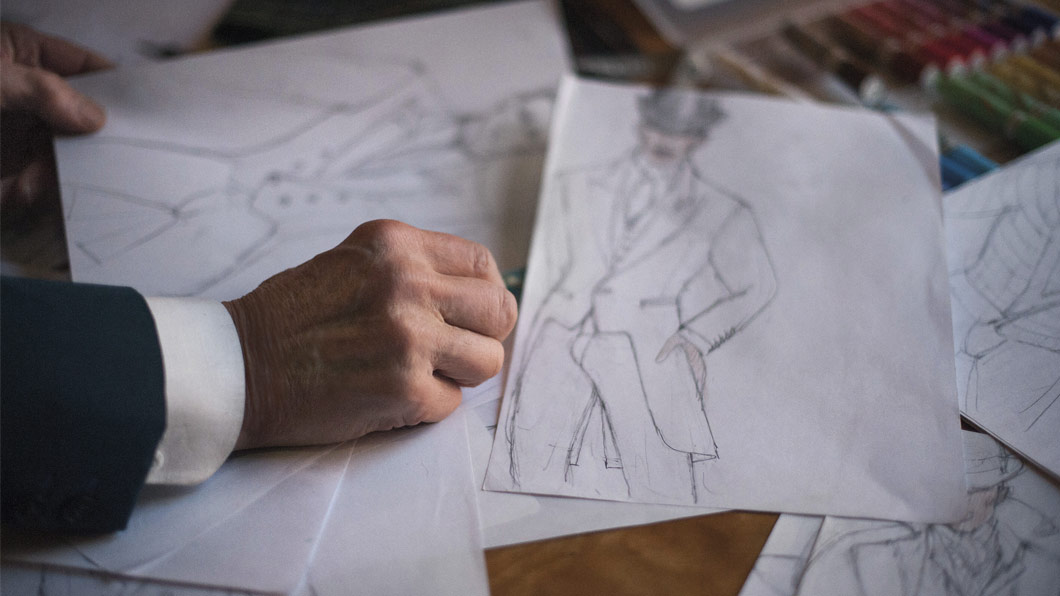

How do you maintain loyalty to tradition and heritage, while continuing to be inventive?

The word I use is ‘evolution’ and edit; you can’t sell a bag which weighs 33 kilos itself when the allowance is 24 kilos for a flight. We have had to find materials that are lighter weight; people don’t travel like they used to – you don’t need a huge quantity of clothes. They wear sweaters, jeans and t-shirts, not formal wear jackets and even a sweater is a much lighter weight product than it used to be.

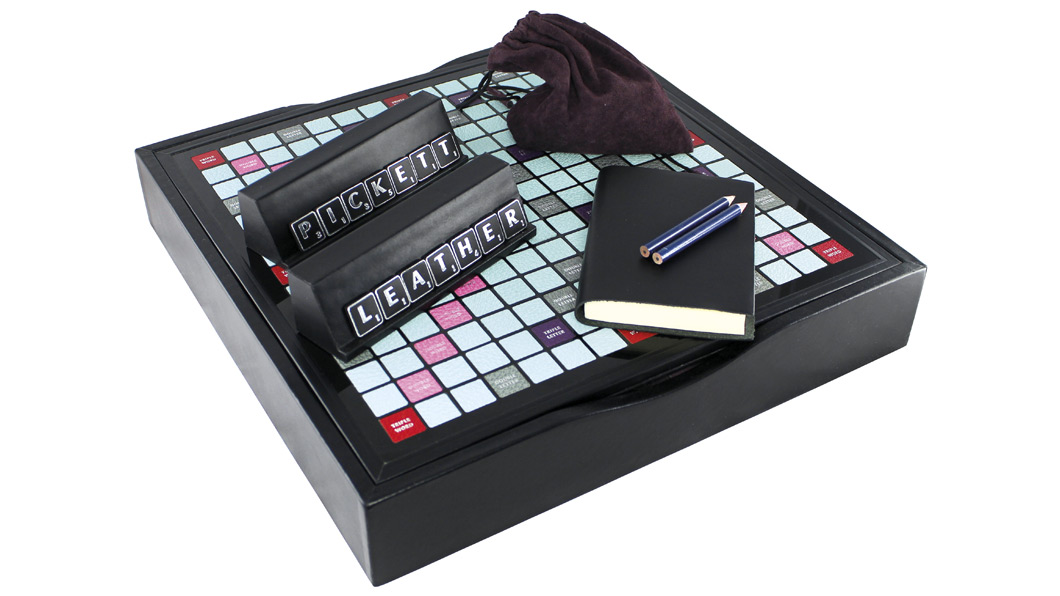

As well as luxury leather goods, you offer a lot of different types of games. Tell us about them.

We make a diverse range of games sets and boards – all the classics – chess, perudo, backgammon, dominoes, poker dice, cribbage, scrabble and bridge. It’s all about getting families together around a good game rather than everyone being stuck to their phones or glued to the telly. All our sets are handcrafted in different sizes and leathers. We pride ourselves on the huge range of colours we do – we’re launching all our games in our new burgundy. This colour will be used across our full range with a new burgundy collection available soon to celebrate our 30th anniversary.

Pickett has created luxury versions of Scrabble

You recently held a games evening at your store on Burlington Gardens. How did that go?

Our games evening was a great success. We had backgammon, perudo, dominoes and chess set up in our Queensbury room at the Burlington Gardens shop. It was quite the tournament and fun was had by all – an overall winner was crowned, and we gave away one of our roll-up backgammon boards as a special prize.

What do you particularly enjoy about your job?

I’ve been doing it for almost 40 years now which is quite scary. Yikes! That makes me feel old (I am not quite on a Zimmer frame yet and proud I swam a mile yesterday!) I think I enjoy the customer service the most. I like serving customers and I enjoy the product design side. We’re a small business so I do feel a bit pulled sometimes, but I do like the variety and opportunity.

Away from work, what do you like to do? What interests you?

Entertaining, cooking, seeing friends. I used to ride but I no longer have five horses, although friends always have horses that need exercising, so I have a ride or a day’s hunting and the occasional riding holiday. I’ve recently discovered triathlons so I’m enjoying my training, probably more than the event though that is the focus – in fact, I’m going a bit bonkers on exercise which will not surprise those who know me well. I am an all-or-nothing sort of person. My main passion is the arts across all genres. Theatre, galleries and music are all interesting to me. I’m always up for a new challenge.

How would you sum up your approach to business in three words?

Business is not my strong point… but I am quoted as saying my business is my pleasure, my pleasure is my life.

Trevor Pickett looks back over his 30