Walk this way

Burlington Arcade, Mayfair’s most elegant shopping destination, celebrates its 200th birthday this year. Tim Newark reveals its secret history.

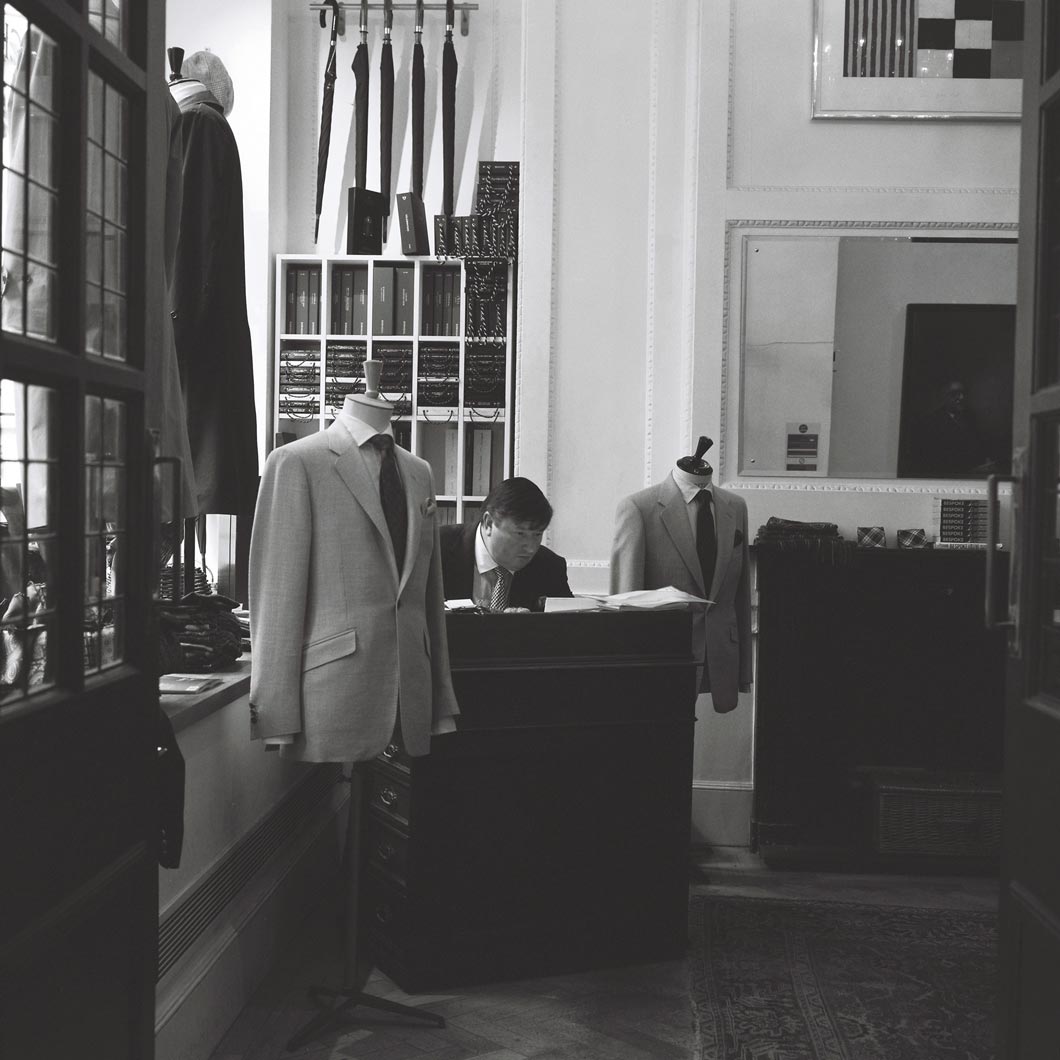

Burlington Arcade is celebrating its 200th birthday on 20th March 2019 and Savile Row is at the very heart of its enduring exclusive style, providing the uniforms for its handsomely attired security force of beadles.

“Keith Levitt at Henry Poole in Savile Row is the gentleman who looks after the Queen’s Livery worn by the royal coachmen and us, designing our uniforms,” says head beadle Mark Lord. “They’re Keith’s interpretation of the uniforms of the 10th Hussars and what a footman would have worn at a stately home. It’s a cherry-red waistcoat, frock coat navy blue with silver trim, trousers black and in the winter, we wear a cape of the kind that cavalry troopers would have worn.”

Burlington Arcade was the ingenious idea of Lord George Cavendish, younger brother of the 5th Duke of Devonshire, and one of the first covered shopping streets in Europe. Like all aristocrats at the time they recruited their own regiments and Napoleonic War veterans of the 10th Hussars were among the earliest beadles patrolling the arcade. Their widows were encouraged to manage some of the shops.

It’s said the arcade was built to stop revellers throwing empty oyster shells into the gardens of Burlington House. “There is some truth to that,” says beadle Mark Lord. “Old Bond Street was full of riotous drinking and gambling clubs where the fast food of the day was oysters from the Thames Estuary. Many of these establishments disposed of their shells by dumping them over the wall into Burlington Gardens. The smell could be terrible in the summer and one of the reasons why the arcade was built was to stop this culinary fly-tipping.”

But it also appealed to the wife of Lord Cavendish as an exclusive place she could shop with her friends. Designed by architect Samuel Ware, Lady Cavendish is believed to have had some input into how the arcade looked, demanding variations in the frontages of the original 72 shops. “She didn’t want steps either,” says Lord, “which is why the arcade is on a slope – a nine-foot incline from Piccadilly to Burlington Gardens”.

It turned out to be an excellent investment too, attracting a fashionable elite of shoppers throughout its first decades in Regency and Victorian London. Other arcades in Mayfair followed in its wake, including the nearby Piccadilly, Princes and Royal Arcades, all elegant places to visit but Burlington remains the premiere historic shopping mall in London.

When the arcade first opened the tenants lived above and beneath their shops. Kitchens were in the basement, storerooms and bedrooms on first and second floors. Most shops are just nine feet deep.

Dark secrets

These tunnels partially survive now and Mark Lord took me to see one section. Stepping down the tight staircase from the showroom, we were suddenly back two centuries, walking on the original flagstones beside an iron kitchen range and peering out the basement bowed window into the gloom of the subterranean delivery passageway. It was then that Mark Lord told me other dark secrets of Burlington Arcade.

Customers were not allowed to carry large parcels inside the arcade. Anything more cumbersome than a small discreet purchase could not be taken directly out of the shop. It had to be brought to you and that came via one of the arcade’s great secrets.

Beneath the main walkway on both sides of the arcade were underground passageways that ran the entire length. Boy and girls would run along these underground passages to bring the parcels to your servants at the entrance of the arcade or take them all the way to your London address. “It has always mirrored the prosperity of the city,” explains Lord. “If London’s booming, the arcade is booming, but when recession hits as it did in the past, some shopkeepers looked at the rooms above their shops for an alternative income.”

Female and male prostitutes would not do anything as crass as directly solicit among the shoppers in the arcade but there was a definite system of attracting clients.

“Sometimes during the summer, they would lean out from the top windows making a clicking noise to interest passers-by,” reveals Lord. “A client would walk into the shop to make a purchase, take it upstairs to present it as a gift for the time of the lady or gentleman they desired and then they would sell it back to the shop to get their money. On other occasions they might hang a stocking from the upper windows.”

The most infamous sexual entrepreneur was one Madame Parsons who had lived her entire adult life as a woman. She died in her bonnet shop in Burlington Arcade and when a doctor arrived to process the death certificate she was identified as a man.

In Victorian London homosexuality was illegal but the police would turn a blind eye if one of the parties dressed as a woman. In that way, homosexual couples could see each other. There was a notorious beadle, George Smith, who got the sack for allowing these activities. “The beadle that gave us eternal shame,” sighs Lord.

A beadle for 16 years in Burlington Arcade, Mark Lord is joined by four others during the week.

“Technically the Metropolitan Police should ask permission to come through the arcade,” he says. “We’re not a real police force but we do enforce rules and regulations based around behaviour. You’re not supposed to whistle in the arcade as when it first opened there were criminal gangs of boys around who would whistle signals to alert each other.”

Famously one of the exceptions to the rule is Sir Paul McCartney who once had his Apple Company around the corner in Savile Row. Other rules still applied include no running in the arcade, no bringing in an open umbrella, no bicycles, no playing musical instruments. “You are not allowed to show merriment,” says Lord, “which is a polite way of saying drunkenness”.

Today Burlington Arcade attracts over four million visitors a year. In May 2018 it was bought by property tycoons Simon and David Reuben for £300 million, who no doubt will only want to enhance the reputation of the arcade for top-end shopping.

“For 75 years N.Peal has been selling cashmere and other luxury fashion,” says Lord. “Jewellers Richard Ogden have been here since 1952, when the upper part of the arcade had just been rebuilt after bomb damage in the Second World War. His son Robert Ogden has been coming here all his life. When a shop comes here, they tend to stay.” A previous trader at the Ogden premises was the infamous Madame Parsons.

Famous shoppers range from Fred Astaire and President Clinton to Naomi Campbell and Arnold Schwarzenegger, who has a particular passion for the arcade’s shoe shops.

Like everywhere else, multinationals such as La Perla, Chanel and Mulberry have also moved in alongside the independents.

Burlington Arcade is also not just about shopping. Many nearby business people find it a quiet oasis off Piccadilly where they can have a relaxing 10 minutes having their shoes polished by long-time resident shoe shiner Romi Topi. Proposals have made in the arcade and there’s even been private romantic dinners.

Burlington Arcade looks perfectly set to entertain London visitors for at least another 100 years.

Tim Newark is a historian and journalist and author of The In & Out: A history of the Naval and Military Club.

Burlington Arcade, Mayfair’s most elegant shopping destination,

Deprecated: Function get_magic_quotes_gpc() is deprecated in /home/domains/vol2/233/2820233/user/htdocs/wp-content/themes/newsroom/framework/lib/eltd.functions.php on line 238

Deprecated: Function get_magic_quotes_gpc() is deprecated in /home/domains/vol2/233/2820233/user/htdocs/wp-content/themes/newsroom/framework/lib/eltd.functions.php on line 238

Deprecated: Function get_magic_quotes_gpc() is deprecated in /home/domains/vol2/233/2820233/user/htdocs/wp-content/themes/newsroom/framework/lib/eltd.functions.php on line 238