By Marie Scott

Also described as the Golden Land, Burma positively sparkles with the precious stuff, pagodas dominating the landscape and covered, ornamented, and filled with it, including solid gold statues of the Buddha.

As the traveller flies in to Rangoon, or Yangon as it is now known, this preponderance of large and small pagodas is all too visible from the air, glittering peaks emerging from the countryside in all directions. And once in the city, more are to be seen, and dominating them all, the huge Shwedagon pagoda and complex, a quite stunning manifestation of the Buddhist faith that informs the Burmese way of life.

We arrived in this teeming city, in the vanguard of what is sure to become a tidal wave of visitors, as the country begins to open up after a half century of isolation. Leaving chilly, wintery London and arriving to find welcoming temperatures in the 80s, we were immediately enveloped into a colourful, congested, and cheerful ambience. It is at once foreign but friendly, and the natives, male and female, are all elegantly attired in the traditional longhi skirt, with nary a fat figure to be seen.

A backdrop of old colonial buildings, largely gone to seed, is a reminder of Britain’s colonial rule here. The British left in 1948 and after a brief few years of democracy, the country came under the iron rule of the generals, who have effectively kept the country poor and cut-off since 1953. Now, still there but relaxing their grip slightly since 2011, the future for Burma may not yet look golden but improvements are on the way.

Tourism is helping. Cruising down the Irrawaddy River on the de luxe ‘Road to Mandalay’ ship, it was clear to see the benefits it brings to locals along the way. With few hotels, as yet, outside of Yangon, this vessel takes travellers to villages eager for visitors and the money they bring. And particularly impressive was the hospital that the ship’s owners, the Orient Express, has helped to fund, the ship’s doctor and assistants seeing some 500 patients a day during the three days the ship is moored at Mandalay.

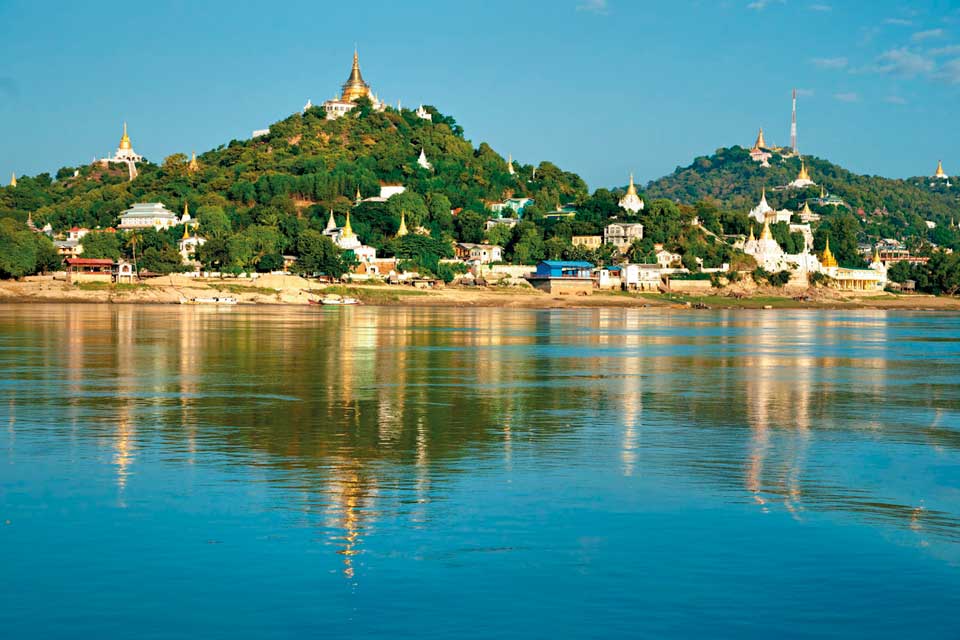

Ah, Mandalay, that fabled city made famous by Kipling, with some help from Sinatra. Now a pretty dusty town with frantic motorcycles and heavy lorries along the infamous Burma Road, its harbour still lives up to Kipling’s evocative poem – though he never actually visited here. Sitting on deck and watching the rays of the setting sun light upon all the golden pagodas on the hillside is magical, especially with a suitably exotic cocktail to hand. Such was taken almost – almost – for recuperative reasons, after a long day out exploring.

An early start took us up through the Highlands to Maymyo, founded by a Colonel May in colonial days as a retreat from the heat of Mandalay. A mini replica of a British country town, its neat villas and bungalows are now largely occupied by rich Chinese and Indians, its town clock, a testament to its British clockmaker, Purcell, still keeping time.

The journey up was spectacular and a reminder of how lush this country is. Everything thrives, flowers, vegetables, fruit in abundance. The country is also rich in oil, minerals and rice, all of which are exported – but with little benefit to the Burmese people. The stark poverty of most makes their elegance, charm and friendliness all the more remarkable, with little pressure on visitors to buy their wares. Women often have faces painted with taneko, a white cream substance; while some of the more fashion-conscious young men sport the tufted hairdos of popular Asian footballers.

Football is a national obsession, the poorest villages sporting satellite dishes to ensure TV reception of international games. It was introduced into the country by a buccaneering British adventurer-turned-colonial-official, one George Scott, in the 1870s. He was responsible for opening up and mapping much of the country, a fearless fellow out of a Boys Own adventure story, who used football to engage with some of the country’s most savage natives, including head hunters. (It’s claimed that this practice only finally died out in the 1970s.)

There is still conflict going on, between the Burma army and the Kachin and Shan ethnic minorities in the north east of the country, and the terrain has changed little since Scott’s time. Here, various warlords reign over an international drugs trade that crosses the border into China, and the region is certainly off-limits to tourists, a pretty lawless place for any visitor.

Back on board our floating hotel, we enjoyed the tranquility of the Irrawaddy, or more properly the Ayawady as the Burmans call it. Drifting gently along, we passed villages and temples, scattered dwellings along the banks, villagers washing and playing in the water, the occasional giant Buddha a reminder of the important place this religion occupies in Burmese life. At one village we visited, a pagoda had recently been renovated with gold, and the £40,000-plus expense was largely covered by nearby residents, who might well be thought to be rather more in need themselves.

But if we had seen many pagodas along the way, Pagan provided a positively wanton abundance of them. Big ones, small ones, some as large as pyramids, some solid, some hollow, some plain, some lavishly ornamented, glittering of gold or mellow of stone, they sprouted across the plain like a forest of fairytale creations. We scrambled up the largest, a pyramid-type giant that became a teaming mass of tourists over its many ledges, there to witness and, more specifically, to photograph the view as the sun set.

Burma is much more than the sum of its many pagodas (Pagan alone boasts over 2,000). It has had a long and turbulent history, and encompasses a rich mix of ethnic races, providing a variety of skills and crafts. In Yangon, the street stalls sell all manner of produce, the indoor markets rich pickings of textiles, apparel and handicrafts. There is fine art as well as local paintings, wonderful gems, traditional lacquer ware, tempting antiques. And all engagingly presented by these delightful people.

Returning to Yangon, we visited a war graves cemetery, where some 27,000 British and allied servicemen are buried at just one of the three sites in the city. Beautifully mantained, the row upon row of marble head stones testified to the youth of so many buried here, and the inscribed messages from loved ones conveyed their anguish all too movingly.

And from one sad experience to another, we were taken to view three ‘ceremonial’ elephants, their confinement something of a metaphor for the lives of the Burman people. Perhaps they too may soon enjoy greater freedom.

Marie Scott travelled with Audley Travel, on Qatar Airways, staying at the Traders Hotel in Rangon, and sailing on the ‘Road to Mandalay’ ship, with a single cabin. Over 12 days, the trip costs around £6,000.