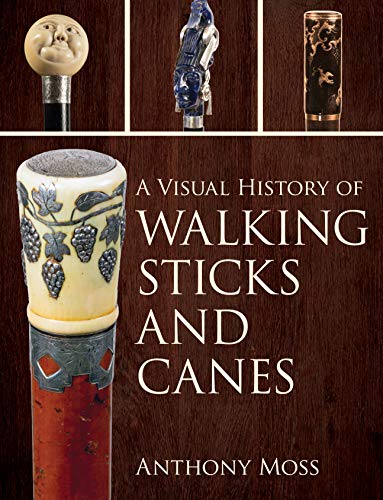

BOOK REVIEW – Walk this Way! – ‘A Visual History of Walking Canes and Sticks.’

Anthony Moss is a rabid rabologist, writes Robin Dutt. Now, that word might conjure images of something biological, chemical or certainly dangerously esoteric. It might suggest someone with an expert knowledge. It may also to some minds, convey the idea of the kind of character typified by Hannibal Lecter. But if this might also be a question of passion and voraciousness in general, then one comes close to the mark, for a rabologist is the distinct word, or term for a collector of walking sticks.

Some only three hundred years ago, gentlemen wore swords at their hips as marques of distinction and choice (not just for street fighting or to defend honour) and of course, were representative of their spending ability. In many ways, the walking stick replaced the sword just as in the 20th century the walking cane would be superseded by the umbrella – a device that provides two functions yet at a push (quite literally sometimes) could still be deemed as a weapon of first defence. Umbrella point and eyes or privates of attacking thief? No contest if it is in the right hands – like someone with some fencing experience. And indeed, the umbrella itself – a relative of the stick – has now been replaced by and large…by nothing. Sartorial justice.

Some only three hundred years ago, gentlemen wore swords at their hips as marques of distinction and choice (not just for street fighting or to defend honour) and of course, were representative of their spending ability. In many ways, the walking stick replaced the sword just as in the 20th century the walking cane would be superseded by the umbrella – a device that provides two functions yet at a push (quite literally sometimes) could still be deemed as a weapon of first defence. Umbrella point and eyes or privates of attacking thief? No contest if it is in the right hands – like someone with some fencing experience. And indeed, the umbrella itself – a relative of the stick – has now been replaced by and large…by nothing. Sartorial justice.

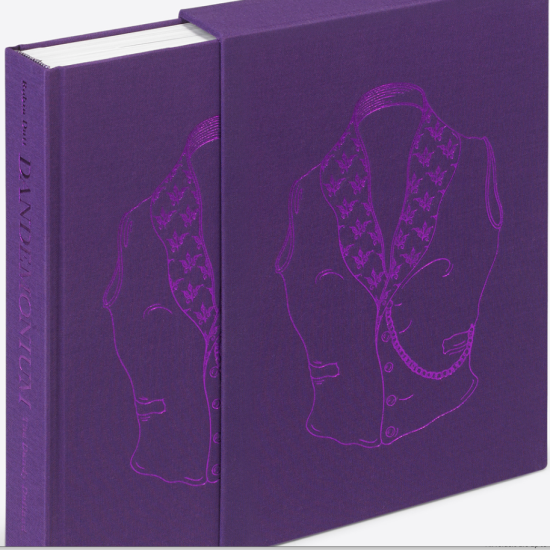

In his very entertaining tome, ‘A Visual History of Walking Sticks and Canes’, Anthony Moss, pictured left, also an esteemed collector of first editions, fine furniture and unusual stationery items, takes us on a fascinating historical journey of this one-time sartorial and purely functional implement which only a hundred years or so ago was a daily feature not to say, a must. The functional stick or cane is one thing, such as a sturdy walking device or something with a curved end held in the hand of a shepherd boy, so to speak and Moss covers some of these examples. But what is most fascinating is the sheer indulgence represented by sticks and canes which were the ‘pointe finale’ when it came to fine dressing for a gentleman or a lady. They really were the finishing touch and betrayed much detail about the wearer (the correct term – for you don’t carry a cane) and also of the quality of the usually commissioned item. In the final analysis, an elegant cane was not simply for the joy of the wearer it was for the admiration of the discerning. And the covetous.

In his very entertaining tome, ‘A Visual History of Walking Sticks and Canes’, Anthony Moss, pictured left, also an esteemed collector of first editions, fine furniture and unusual stationery items, takes us on a fascinating historical journey of this one-time sartorial and purely functional implement which only a hundred years or so ago was a daily feature not to say, a must. The functional stick or cane is one thing, such as a sturdy walking device or something with a curved end held in the hand of a shepherd boy, so to speak and Moss covers some of these examples. But what is most fascinating is the sheer indulgence represented by sticks and canes which were the ‘pointe finale’ when it came to fine dressing for a gentleman or a lady. They really were the finishing touch and betrayed much detail about the wearer (the correct term – for you don’t carry a cane) and also of the quality of the usually commissioned item. In the final analysis, an elegant cane was not simply for the joy of the wearer it was for the admiration of the discerning. And the covetous.

Naturally, a couple of centuries ago there were cane shops, rather like ready to wear clothing stores much later on, where those without the means but with dreams of being, could give a semblance of the elegant look. If they were imaginative and tied a silken ribbon around the stick’s collar, for example, or even go further and apply some sort of paste jewel themselves (it must have happened) well, all to the good. At least it was personalized. But the world of the commissioned cane is quite another affair.

Moss is keen to point out that the stick or cane is far beyond ‘a mobility aid’, unless of course, one thinks of that mobility classic of old, the hooked hospital stick for the injured young or the otherwise healthy old with NHS burned into the handle. Ironically this could look like a person’s initials but quite unlike the curlicue swirls or strident block lettering commissioned by the owners themselves. I recall that it wasn’t so long ago that a certain eccentric of London’s Harrow Road used to appear from time to time with a radio perched on his shoulders blaring a Reggae tune and his battered top hat and long black cane festooned with flashing lights. It was his sceptre, his staff of office. A symbol of sorts. And indeed, what was a pharaoh without his sceptre? Can Parliament itself be called to order, when the occasion demands, without Black Rod?

Moss’ knowledge is devastatingly wide – explosively so – and his passion unbridled. He is probably one of the most important cane collectors in the world and this book surely represents his life’s real work. And it all started when his delightful poetess wife, Deanna presented him with a couple of sticks as a present one day so long ago in their 56-year marriage. Did she know then what she was doing? Probably. For the A&D Collection is one of the finest to be enjoyed and within the covers of this book can be appreciated by all, enthusiasts and the curious. The trouble with curiosity is that it can sometimes lead to collecting. Ask Mr Moss.

Moss’ knowledge is devastatingly wide – explosively so – and his passion unbridled. He is probably one of the most important cane collectors in the world and this book surely represents his life’s real work. And it all started when his delightful poetess wife, Deanna presented him with a couple of sticks as a present one day so long ago in their 56-year marriage. Did she know then what she was doing? Probably. For the A&D Collection is one of the finest to be enjoyed and within the covers of this book can be appreciated by all, enthusiasts and the curious. The trouble with curiosity is that it can sometimes lead to collecting. Ask Mr Moss.

Illustrated with over 800 full colour superbly considered photographs by Gayle Bromberg who was, at first meeting with Anthony, ‘bowled over’ by his passion, one might reasonably expect a visual feast. So here we have all types of sticks and canes, from canes with provenance to shooting sticks, rat catching canes to map canes, defence sticks to decorative essentials, hollow structures that conceal folding violins or ones that harbour poisons. Then, there are ‘squirter’ canes – devices filled with water to titillate or annoy ladies in the music hall. Others are set with watches, compasses, matchboxes and so the list races on… Perhaps today we might set one with a Sat Nav or a step counter or a device to keep up with the latest data on the Omicron strain? Mayhap the past had its version of all of these things.

Exquisite carving of exotic heads in wood or in ivory, such as the spectacular example of Napoleon, silver ladies resting leisurely as nymphs on horizontal handles (perfect for a grasped hand) and suggesting poetic verse or pure sex, round balls of smooth marble or glowing amber and the fantastic bejewelled examples from the studios of long gone artists of such rare talent – all will delight and amaze.

Mr Moss has done more than a good job. You can’t take a stick to him.

‘A Visual History of Walking Sticks and Canes’ by Anthony Moss is published by Rowman & Littlefield. £58.