Malcolm Folley with David Coulthard in Monaco

Award winning sportswriter Malcolm Folley gets under the skin of motorsport’s most fabled race in his new book, Monaco – Inside F1’s Greatest Race. The book is not a conventional history but rather a companion of stories and shared memories from those most intimately associated with Monaco such as Sir Jackie Stewart, Niki Lauda, Damon Hill, David Coulthard, Ross Brawn, Martin Brundle, Nico Rosberg and many more, including the most unlikeliest winner of all, Frenchman Olivier Panis.

The day Lauda had Senna in his sights

The entrance to the Automobile Club de Monaco is located on Boulevard Albert 1er, barely 100 metres from the first corner of the circuit, Sainte-Dévote. In the foyer is a portrait of His Serene Highness Prince Albert II and his wife, Princess Charlene; indeed, portraits of the ruling monarchy are omnipresent throughout the principality. Poignantly, before you reach the ground-floor restaurant, there is a painting capturing the alluring beauty of Prince Albert’s mother, Oscar-winning actress Grace Kelly, which is a reminder that her marriage to Prince Rainier III, in front of the world’s media in April 1956, elevated the monarchy of Monaco to the global stage as she became Princess Grace.

Beyond the reception desk is a corridor leading to the library. On the right-hand wall is a photographic gallery of winners of the Monaco Grand Prix. A photograph of the late Ayrton Senna is prominently displayed, his rightful privilege as the man who has won a record six times on these streets. Another man whose history is reflected on this wall of fame is Niki Lauda, a victor twice. The careers of the men overlapped as Lauda neared the end of his pre-eminence in the paddock and Senna made his introduction.

Lauda recalls their earliest encounter as though it occurred yesterday. He was in pursuit of his third world championship – with McLaren then – after winning two titles for Ferrari. Senna was in his first season in Formula One in an uncompetitive Toleman. Only Senna knew – knew for certain – that greatness beckoned. It was 1984: in this scene Lauda is Big Brother.

“I was on a quick lap on Thursday . . . and I came round a corner to find Senna driving in the middle of the road,” says Lauda. Back in the pits, Lauda went in search of Senna. His question to the young Brazilian was typically brusque. “Are you one of us?” he demanded.

“What do you mean?” replied Senna. Lauda explained the fundamental requirements – and respect – expected from a new arrival on the most elevated stage in motor racing. “You can’t sit in the middle of the road in qualifying,” said the Austrian. He had a manner that did not invite debate.

Senna was unusually self-assured, though. “Niki,” he said. “This is the way I am.”

Lauda left without another word. In qualifying on Saturday, he knew his moment would arrive. “I did my quick lap and stayed out,” he said. “I was looking in my mirrors and waving drivers through. Then I saw Senna approaching from out of the tunnel. I stopped my car in front of his. After Senna stopped I took first gear and went. In the garage I waited for him to come to me this time. He did.”

Senna began to make his feelings known, when Lauda interrupted him. “Ayrton,” he said. “That’s the way I am.”

Great rivals Niki Lauda and Ayrton Senna showing some mutual respect

The Austrian, these days a driving force behind Hamilton’s acceleration to greatness with Mercedes, has never compromised his individuality in a sport that long since surrendered its personality to corporate conformity. Lauda has never been measured for a team uniform. “Senna had a belief that he was right, but I told him that I could do the same if that is what he wants,” he explained. “From this moment, we never had a problem.”

To trace the winners at Monaco, from Juan Manuel Fangio to Stirling Moss, to Graham Hill and Jackie Stewart is to follow a lineage of motor-racing aristocracy which runs through the labyrinth of these streets to the barons of the sport these past 40 years: Lauda, Prost, Senna, Schumacher, Alonso, Hamilton, Vettel and Nico Rosberg, all world champions bar Sir Stirling, and all multiple winners at Monaco.

Hamilton always claims to feel the spirit of Senna infiltrate the soul of his driving when he is negotiating the swift changes of elevation, and tight, twisting corners around the harbour after screaming on the rev-limit through the artificial light of the tunnel. The first of his two victories, in 2008, the last win in Monaco for the once invincible McLaren team, evoked an outpouring of emotion from Hamilton that perhaps will never be surpassed no matter how many times he wins the world championship.

Monaco mattered because of Senna, yes; but, more, because of its historical significance to all who have driven a Formula One car on these streets normally governed by a 50kph speed limit, or less.

When every night was party night

Michel Ferry is a link to the past and more pragmatic present in Monaco, where a Grand Prix has been held uninterrupted since 1955. Beside his desk in the inner sanctum of the ACM is a photograph of him with Prince Rainier, and another with his son Prince Albert II. Ferry, aged 72, a silver-haired, debonair Monégasque, who is Commissaire Général of the Monaco Grand Prix, has held office within the ACM since 1962.

He recalls with fondness the days of Stirling Moss, who won three times on these streets, and Graham Hill, who wore lightly the epithet Mr Monaco, given him for winning five times between 1963 and 1969. “It was another time, a different way of life, a lot of fun,” says Ferry. “Every night there was a big party with the drivers. Graham was at the Hotel de Paris on Friday and Saturday nights. Drivers were playing cards and drinking.”

Stewart and his wife, Helen, were an exception, says Ferry. “The couple were very close with Princess Grace,” he explains. “They were received at the palace and stayed there, more than once, during the Grand Prix.”

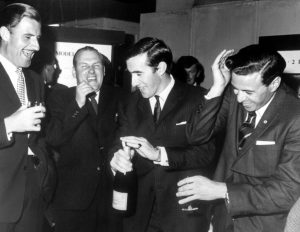

Jackie Stewart opens a bottle of champagne rather more sedately than usual, much to the amusement of fellow Formula One drivers Graham Hill and Jim Clark, and Provost John Campbell of Dumbarton

In contrast, the late, colourful James Hunt never knowingly missed a party in the Seventies. Remembering them was another matter. “James smoked drugs – everybody knew that,” says Ferry. “Lots of girls were around. The access to the track was free. You could approach the drivers, you could touch the cars. It is finished like this today: the cars arrive in the pits and the teams close the doors. Today you need to ask ten people to apply for a pass!”

For some years it has been evident that the only people not partying in Monaco until after the flag has dropped are the drivers. With car manufacturers Mercedes, Ferrari, Honda and Renault investing at least $1 billion in Formula One between them, that is the least surprising factor of Monaco over a grand prix week.

Each year the armada of ocean-going yachts and floating palaces that motor into the harbour becomes larger and more ostentatious. Often these boats are registered in tax havens. It is rumoured – but never openly admitted – that oceans of money exchange hands to claim a prime berth on the quayside during the grand prix weekend. It is the race every Formula One driver most wants to win; and for those with power and influence it is the race to be seen at.

Celebrities from down the ages, including Frank Sinatra, Cary Grant, Bing Crosby, The Beatles, Sylvester Stallone, George Clooney and Brad Pitt, have been seduced by this motor race by the shores of the Mediterranean.

As veteran broadcaster and PR executive Tony Jardine suggests: “Monaco is the glittering prize because everything associated with Formula One is epitomised in Monte Carlo: boats, champagne, success and excess.”

Monaco: Inside F1’s Greatest Race by Malcolm Folley is published in hardback by Century, available to buy from Amazon or any good book store now, priced £20.00