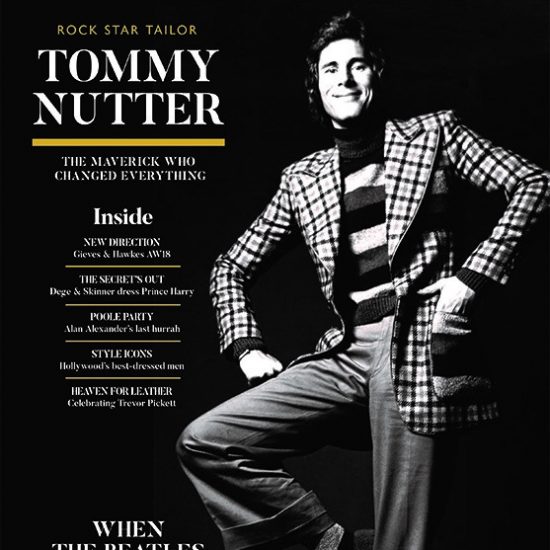

Philip Norman remembers the days when he watched the Fab Four try – and fail – to run their business operations from London’s most fashionable address

Number Nine Savile Row is a Georgian house in the heart of Mayfair’s bespoke tailoring district. Nowadays, it’s a trendy children’s clothing store, but 50 years ago it became one of London’s most famous buildings as the HQ of the Beatles’ Apple organisation.

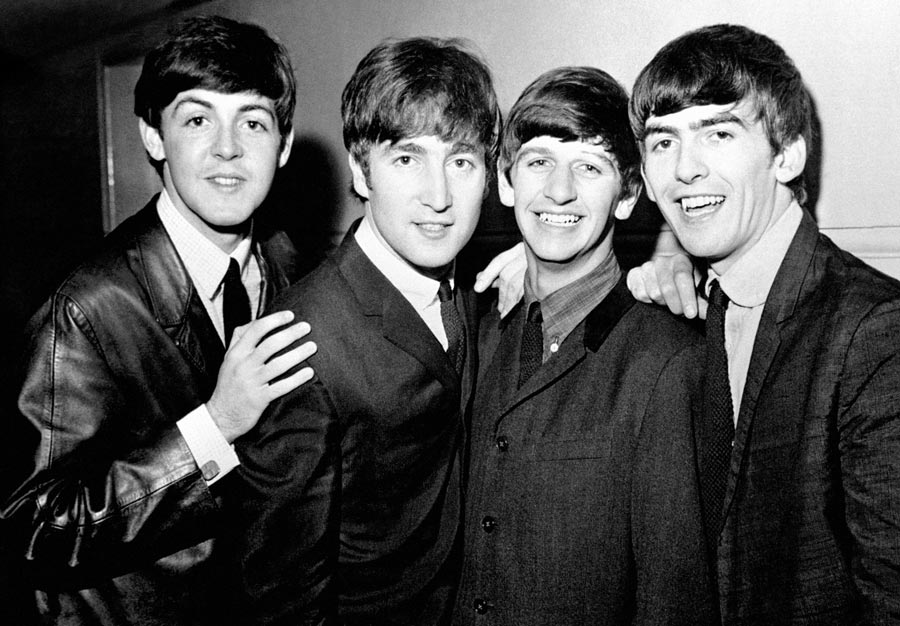

Here, John, Paul, George and Ringo made their brief, disastrous attempt to become business tycoons; here, too, they effectively broke up in 1969, although the official split didn’t come until two years later. And, while the double crisis unfolded and those closest of friends turned to bitter boardroom opponents, I was inside the house, watching it happen.

I sat with John and Yoko Ono — then playing her own not inconsiderable part in breaking up the Beatles — while they planned to give their next press conference with sacks over their heads.

I talked to George as he tried on expensive Mr Fish shirts for a photo session, and was presented by Ringo with a jar of apple jam made by his then wife (and George’s future lover), Maureen.

I had breakfast with the Beatles’ terrifying new American manager, Allen Klein, as he fought to keep the band together until he could sign them to a massive new recording contract.

And every day I witnessed the Beatles’ business being plundered by swarms of con artists and freeloaders like wasps around a Grade II-listed honeypot.

Apple sprang from their desire to have their own record label, rather than be tied to the elephantine EMI organisation, and take control of the many other commercial activities being carried on in their name, like music publishing, filmmaking and merchandising. Fortuitously, EMI owed them £2million in back royalties (multiply by 10 for today’s value) which was to be paid in a single instalment. The only way to avoid losing almost all of it under the then Labour government’s punitive tax regime was to invest it in a business. But they were the Beatles, so it couldn’t be just your everyday grim, grasping kind of business.

Paul McCartney defined their aim as “a kind of Western Communism … We’re in the happy position of not needing any more money,” he said, “so for the first time the bosses aren’t in it for profit.” Befitting the hippy era of love and peace, there was to be a strong philanthropic and what today would be called mentoring element. “We want to help people but without doing it as a charity. We always had to go to the big men and touch our forelocks and say: ‘Please can we do so and so.’ If you come to me and say: ‘I’ve had such and such a dream,’ I’ll say to you: ‘Go away and do it’.” Art connoisseur Paul came up with the name Apple and a logo inspired by the Belgian surrealist Rene Magritte’s 1966 painting Le Jeu de Mourre (The Guessing Game) of a pristine green Granny Smith with Au revoir written across it. In a Lennonesque pun, the organisation’s full name was Apple Corps, pronounced “Core”.

Schizophrenically, as it took shape, its four bosses were in India, studying transcendental meditation with their guru, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, being taught the futility of earthly possessions at one moment and signing business contracts the next.

The organisation began modestly with a publishing company, Apple Music, on the upper floors of a building in Baker Street. Its ground floor then became an Apple boutique, the first in a projected chain, selling hugely expensive hippy robes created by a Dutch design collective calling themselves The Fool. They also covered the building’s exterior with a psychedelic mural which caused such outrage among other Baker Street traders that it had to be scrubbed off, removing a potential tourist attraction to rival Sherlock Holmes.

Managed by John’s old school friend, former policeman Pete Shotton, the boutique lacked any retailing expertise and quickly turned into a shoplifters’ paradise. After a few months, the Beatles terminated it by giving away its entire stock (after themselves taking first pick.) Late in 1968 came the move to 3 Savile Row, which had formerly belonged to the bandleader/impresario Jack Hylton and was purchased for what was even then a bargain £500,000. From day one, a crowd of female fans clustered around its front steps, whatever the weather, monitoring every arrival and departure and erupting into demented screams if it happened to be a Beatle.

George, the least fan-friendly of the four, ungraciously dubbed them Apple Scruffs. But they wore the name with pride, even producing their own newsletter headed Steps, 3 Savile Row. To begin with, the house’s vibes (a favourite Apple word) seemed all good.

Paul, a born producer and A&R man, took charge of the record company with its Apple-logo-ed label, working with Peter Asher, the brother of his then girlfriend, Jane Asher, and formerly one of the pop duo Peter and Gordon. Apple Records put out the Beatles’ controversial but hugely successful double White Album and scored an international No.1 single with Those Were The Days by Mary Hopkin, whom Paul had spotted on the Opportunity Knocks television show.

Every week, it seemed, the media excitedly reported the opening of yet another Apple division, invariably run by some friend or protégé of this or that Beatle. There was Apple Tailoring, Apple Films (whose TV debut, Magical Mystery Tour, was their first-ever flop), Apple Electronics, headed by John’s assiduous courtier “Magic Alex” Mardas, and Zapple, a spoken-word record label for avant-garde poets and writers. There was to be Apple Foundation for the Arts and an Apple school, run by Ivan Vaughan, another childhood friend of John’s, who’d first introduced him to Paul at a church fete in 1957.

The first serious bruise on that shiny green skin was John’s public affair with Yoko Ono, a Japanese-American conceptual artist, and the revelation that he’d left his wife, Cynthia, and small son, Julian, for her. Such was his obsession with Yoko that he insisted she should be at his side every minute of the day, even in the recording studio where no Beatle wife or girlfriend had previously been allowed to set foot. Yoko in effect replaced Paul as John’s creative soul-mate.

In November 1968, Apple Records reluctantly released their first album together, a melange of electronic noise recorded at John’s house while Cynthia was away in Greece. Ironically titled Two Virgins, its cover was a photograph of the couple full-frontally nude. The public were bewildered by what had come over former cuddly mop-top Beatle John while the British Press portrayed Yoko as a witch who’d cast a spell over him.

Then John and Paul, that formerly indivisible entity, were reportedly at loggerheads over the choice of a manager to replace their visionary first one, Brian Epstein, who’d died of a drugs overdose in 1967, aged only 32, when Apple was still on the drawing board. The need was sharpened by a letter from their accountant warning: “Your finances are in a mess. Apple is in a mess.” Paul’s candidate was New York entertainment lawyer Lee Eastman whose daughter, Linda, happened to be the new girlfriend with whom he’d recently replaced Jane Asher.

John, backed by Yoko, wanted Allen Klein, a tough New Yorker of dubious reputation who’d previously managed the Rolling Stones. John had reportedly enlisted George and Ringo’s support in Klein’s favour and Paul, marginalised and embarrassed — for Lee Eastman was soon to become his father-in-law — had walked out of Apple and gone to ground with Linda on his farm in the Scottish Highlands. With that, the tone of Apple’s media coverage changed from indulgent amusement at the Beatles’ “Western Communism” to censure of their naivety and muddle-headedness and rumours of how they were being ripped off by everyone around them.

I was 26 and, in three years of national journalism, had not written a single word about the Beatles. All the Fleet Street papers maintained full-time Fab Four correspondents who’d followed them from the beginning and cultivated personal relationships with them. At my own paper, The Sunday Times, Beatle coverage was jealously guarded by two older colleagues, Derek Jewell and Hunter Davies. On such a crowded bandwagon, how could there possibly be any room for me? Then a friend who was editing New York’s Show magazine asked me to find out what was really going on inside Apple. “Try to set up a picture of all four Beatles around a boardroom table,” he said, little realising the impossibility of such a shot.

So it was that I first met the Beatles’ press officer, Derek Taylor, an ex-Fleet Street journalist with a toothbrush moustache who was the most pursued and courted PR man on earth. Unconcerned by my lack of Beatle-reporting form, the quixotic Taylor granted me special access to 3 Savile Row because of my recent Sunday Times interview with the strongman Charles Atlas, whose bodybuilding course he’d followed as a boy. “Just come in and hang around,”’ he told me.

The house’s elegant interior was the last word in late-Sixties style, carpeted throughout in applegreen, its white walls lined with framed gold discs. All the senior executives had interior-designed offices with furnishings they’d been allowed to choose for themselves. Everywhere was evidence of how freely the Beatles’ money was being spent. The Apple top brass had acquired a taste for a certain brand of vodka available at only one London restaurant, which did not do off sales. Two employees therefore would be sent to the restaurant (by taxi naturally) to eat a full meal, then buy a bottle of the vodka to bring back, again by taxi. The only security was a doorman in a dovegrey frock coat who conducted a love-hate relationship with the Apple Scruffs on the front steps.

Most of the time, the front door was left unlocked, leading to continual opportunistic thefts of typewriters, hi-fi equipment and gold discs. At one point, it was discovered that Post Office messenger boys who delivered telegrams — of which multitudes arrived at Apple in those pre-email, pre-fax days — were systematically stealing valuable lead from the roof.

The problem was that many of the dodgiest visitors were personal friends of a Beatle and so impossible even to remonstrate with, let alone exclude. The previous Christmas, for instance, George had invited an entire chapter of Hell’s Angels from San Francisco, on their bikes, led by two ferocious characters named Frisco Pete and Billy Tumbleweed.

The Angels had virtually moved into the house, drinking, hell-raising and sexually harassing secretaries, immune from all consequences as George’s guests. They’d finally outstayed their welcome by gate-crashing a Christmas party for Apple staff’s children featuring a 42lb turkey warranted to be the largest in Britain and presided over by John and Yoko dressed as Father and Mother Christmas. When the Angels prematurely began devouring the monster turkey, a journalist who reproved them for bad manners was felled by Frisco Pete and crashed into Father and Mother Christmas’s laps. After Paul’s disappearance (so total that rumours began circulating that he was dead), John became Apple’s most visible and available Beatle.

In a front ground-floor office, sharing the same desk, he and Yoko launched the anti-war campaign that would culminate in their “bed-ins for peace”, first in Amsterdam, then Montreal, and bring worldwide ridicule down on their heads.

George and Ringo made irregular appearances, signalled by a big white limo nosing along Savile Row and sudden uproar from the Apple Scruffs.

Klein had already got to work as their manager, commuting from New York with a set of portable filing cabinets. Though he was devoutly Jewish, the Apple Scruffs shouted “Mafia!” as his portly figure hurried into the building, poring over balance-sheets. His time was divided between attempting various company takeovers for the Beatles, renegotiating their soon-to-expire contract with their American record company, Capitol, and attempting to stem the haemorrhage of money from their business.

He immediately axed several Apple sub-divisions and useless executives, along with some useful ones, like Apple Records’ head, Ron Kass, who might have threatened his position. Indeed, Klein was already wondering whether managing the Beatles, the ultimate entrepreneurial prize, might not be a poisoned chalice.

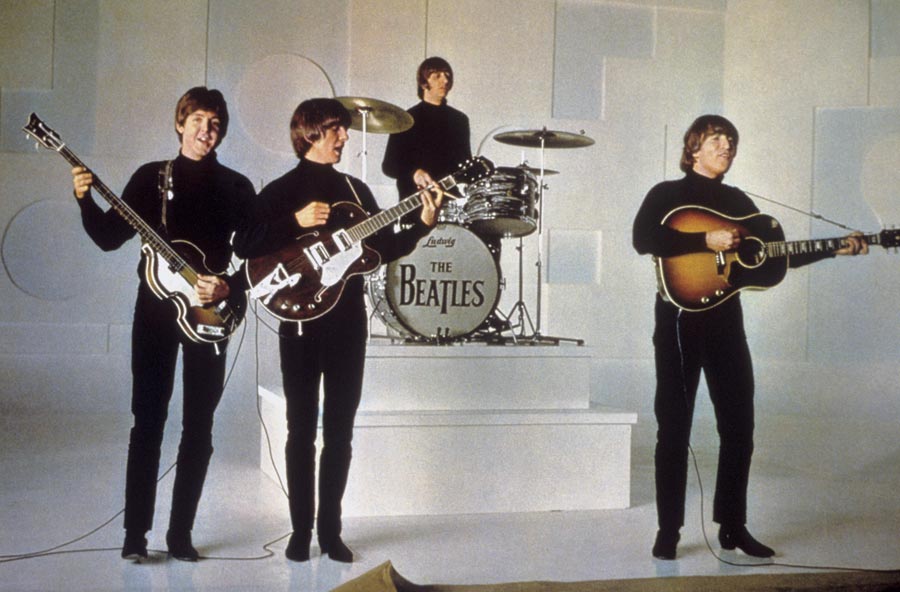

Their next album, Let It Be, was in abeyance after their inspirational producer George Martin had walked out, tired of John and Yoko’s studio canoodling and the bickering between Paul and George. With the album there was to be a documentary of the same name, ending with their first performance together since the time of Hey Jude and Revolution. Suggested locations ranged from a 2,000-year-old Roman amphitheatre in Tunisia at sunrise to the deck of a liner in mid-ocean. It had ended up as a brief recital on the roof of 3 Savile Row — an impatient compromise that became one of their most iconic moments, imitated by other bands for evermore.

The centre of the house was the second-floor press office, where Derek Taylor held court to journalists, music industry figures and an immense variety of less relevant callers, from a wicker chair with a huge scalloped back, liberally dispensing Scotch and Coke and Benson & Hedges Gold cigarettes. The room was kept in perpetual darkness, with the spermatozoa shapes of a psychedelic light show wriggling over the walls and ceiling. Every surface was littered with expensive, pointless executive toys, like a row of little plastic birds endlessly dipping their beaks into a water tray.

Once, I heard a voice on Taylor’s intercom say: “Derek…Jesus Christ is in reception.”

“Oh, God, not that asshole again,” he sighed. “OK, send him up.”

The press office reeked of pot — a major risk with Savile Row police station only a couple of hundred yards away. Taylor’s secretary had been trained to flush the whole lot down the toilet at the slightest sign of a raid. One afternoon when I called, Taylor was trying to arrange a visa for John to take Yoko and their Plastic Ono Band to Toronto to appear in a festival. It was tricky as he had a conviction for possessing cannabis, or “a crime of moral turpitude” as the immigration authorities termed it.

After the Toronto show, John told the London Evening Standard’s Ray Connolly he was leaving the Beatles but made Connolly agree not to run the story for the present. On the flight back to Britain, John also told Klein. So Klein did re-sign them to Capitol Records at a munificent new royalty rate, only to have them disintegrate in his hands. In those days, it was inconceivable that a band could break up, yet still go on selling more and more records with each passing year.

But now it was to happen.

In the Seventies, all the ex-Beatles pursued solo careers while the world waited patiently for them to get over it and reunite. That hope finally ended with John’s murder in 1980, after which a second wave of Beatlemania began that still shows no sign of abating.

Almost as great an asset as the Beatles’ music was their company’s name. When Steve Jobs wanted to use it for his computer corporation, he had to make several multi-million dollar payments to Apple Corps.

Among those who passed through 3 Savile Row in the 1960s was an 18-year-old with a toothy smile, seeking Beatle cash to start a national student newspaper. Later, he was to seize on their idea of a multi-stranded corporation run in a seemingly rock ‘n’ roll way, and take it further than they’d ever dreamed. His name was Richard Branson.

Text © Daily Mail

Images © PA IMAGES