It’s always a win-win with gin, says Robin Dutt

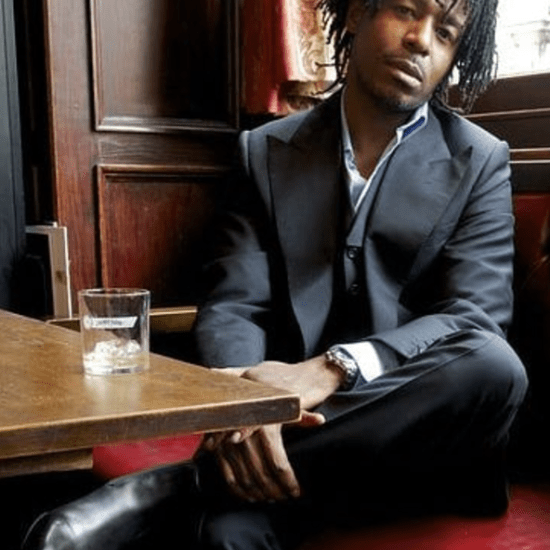

THIS IS NOT A LIE. MY first alcoholic drink was gin. Those who know me are apt to see a vodka martini or a flute of champagne in my hand. But it was gin that seduced me. No tonic was involved at that time. It was the occasion of a school trip to the National Theatre and my dear friend (still is) insisted on buying me something to drink. I thanked him for his kindness and opted for a Coca-Cola. “No, Robin. A drink.” I knew what he meant and, pretty soon, two rocks glasses of gin and fizzy bitter lemon were bejewelling the plain table top in almost Art Deco tones of soapy blue. As we were both only 16 or so, it felt grown up and mischievous.

Gin is a taste you don’t easily forget and, unlike many drinks, most have a clear opinion about it which runs predictably from loving to loathing. Originally created as a herbal medicine (in the way that vodka can be resorted to as an almost first aid for a minor cut) its origins can be traced to the Middle Ages and based on an older Dutch liquor called jenever, deriving from the Latin, “Juniperus”, for Juniper. The essence of this essential berry is omnipresent in the drink and the first whiff as you open a bottle is this. It was a concoction which was apparently drunk before battle to calm the nerves and perhaps that is where the still-used term, “Dutch Courage” comes from. The other popular phrase “Going Dutch” doesn’t have quite the same appeal.

Although not an English invention, it didn’t take the English long to adopt it as the go-to, must have slurp of the day, night and any time in between and, indeed, between 1695 and 1735 literally thousands (around 7,500 in London alone) of gin-shops existed, a period typified as that of the “Gin Craze”. And craze is a good word to use. William Hogarth’s Gin Lane shows gin sodden denizens in a slice of desultory 18th century life displaying the effects of imbibing too much. It also features a baby about to take a headlong plunge from its drunken mother’s arms into an external stairwell, the ominous skeletal man hard by, a crumbling building and the only person prospering, the undertaker. But all this at a time when it was safer not to drink the water. And it is as well to remember gin’s seductive but slow powers in the popular drinkers’ mantra (often ignored, of course, when ordering a gin martini) ‘One Martini, two Martini, three Martini…Floor!’

The sheer variety of gins available is staggering and it seems that, at this very moment, we are enjoying another “Gin Craze” revival. And, while there may not be thousands of specific gin shops, the ancient, classic, modern and explosively contemporary varieties are jostling for centre stage and their time in the bar spotlight or, indeed, the must-have drinks at the openings of fashion boutiques and art gallery evenings. Despite the incalculable varieties, the various ingredients (the botanicals) are responsible for crafting the character for every taste, every style. These, and the liquid’s mercurial clarity, ensure that each gin has legions of fans but then some, a select cognoscenti few. And, despite its foreign origins, the appellation, “London Dry Gin” has a defined meaning and provenance the world over.

Botanicals is a word which in itself is responsible for carving any gin’s identity. For the old school imbibers it cannot be anything but, for example, Gordon’s and, for those who find the presence of dancing herbs on the tongue to their liking, Bombay Sapphire may spring to mind. The Botanist is made with 31 botanicals (22 native to the island of Islay). Hendrick’s has long charmed cocktail fanciers with its cucumber and rose, the garnish – always a slice of the former as long as the high ball, emerging triumphantly through the ice. Sipsmith is from the first copper distillery in London since around the beginning of George IV’s reign. Horse Guards is quite new and the word that is used to describe it is “smooth”. That is its only necessary credential. And you will discover countries of origin as diverse as Canada to Uganda, New Zealand to Germany, the Philippines to America. There are notable gins from France, Italy and Belgium too. And, once again, England, of course.

But, even in the gin-soaked glory days of the past, presentation and public perception of a product was really not even thought about. An earthenware jar with a single curved handle was indistinguishable from another such vessel. Now, as with all drinks, the identity has to be announced from the bar shelves to the bar guests. Shape of bottle, size of bottle (to fit most bar shelves although some are purposefully over-sized), magnetic label colour – red somewhere is often employed, the authority of mono or duo chrome wording, the colour (or not) of the bottle itself, an engaging hand script, the visibility or invisibility of the liquid within and of course, perhaps most importantly, the name. One that becomes generic. And then there is the huge importance of a cocktail name – that sticks, in the way that a Bloody Mary for vodka does. By the by, if using gin instead of vodka it is known as a Red Snapper. But, Fallen Angel, French 75, Moon River, Old Etonian, Satan’s Whiskers, Vesper, Gibson and The Last Word are all, of course, individual, each moniker conjuring a sense of taste, space, time and idea, long before glass has reached lip. Arguably, gin cocktails have the most enigmatic of all alcoholic beverage names. Often they sound like sensory or historical or mischievous adventures.

The gin arena is vast and competitive. But, because of the choice available, with more on the way, almost seemingly every day, there is room for all. But they do stand or fall ultimately. Fashion, while fickle, is a factor. Those brands that can equate with a lifestyle or time or provenance, treat these aspects as preciously guarded hallmarks. Gin is the liquid heart. What exactly characterises it? Sometimes, gins come back from the brink of near extinction because of fashion or companies being bought. New ones are often readily welcomed and give the enthusiastic barman more tools for his alchemy making.

While the definition of a spirit in gin’s case is the prosaic, “a strong, alcoholic drink”, it may be well to look at the other meanings of spirit – not usually applied. “Something’s characteristic quality”, “a person’s mood”, “courage and determination”.

Somehow there is something of a flow between the same word, used for two completely different things.