The widow of Lord Lucan died from a cocktail of drink and drugs after diagnosing herself with Parkinson’s disease, an inquest heard this week as Coroner Dr Fiona Wilcox recorded a verdict of suicide. Police discovered 80-year-old Lady Lucan’s body after forcing entry into her London home last September where she was found on the dining room floor with a pill bottle under her body. Here, Tyne O’Connell, in a piece published in the current edition of Savile Row Style, pays tribute to her friend.

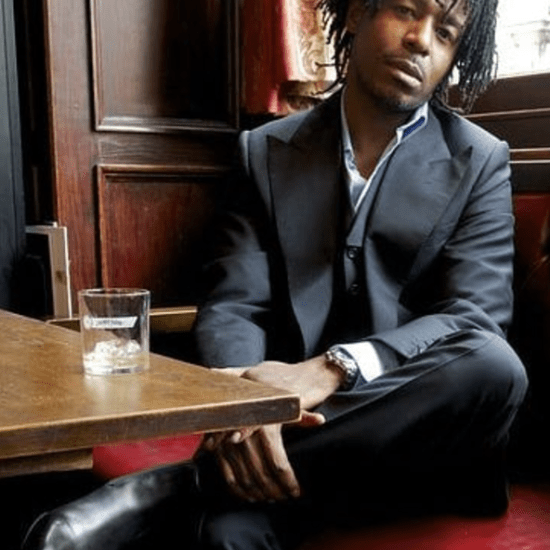

Tyne O’Connell with her friend Lady Lucan

My friend Veronica Lady Lucan was an icon of a lost age, embodying the very best of her generation’s qualities. Her voice was reminiscent of The Queen’s as I remembered it in the 70s when we’d cluster around the television to hear the Christmas speech. Even The Queen was persuaded to modernise her vowels and soften her consonants over time but Veronica still spoke with the sharp precision of a cryptic crossword puzzle. Her old-fashioned intonation was mistaken as imperious but she was extremely humble and suffered with low self-esteem. Dressed in her snappy bespoke Aquascutum shooting suit, trimmed in mink, or any of her bespoke outfits, she always looked as if she had walked straight out of an edition of Tatler. Proof positive that fine-tailoring never goes out of fashion as her wardrobe had been made for her before her world came tumbling down that awful night in 1974.

For it is impossible to speak of Lady Lucan without mentioning the dark shadow under which she lived following one of the most infamous crimes of British history, involving her husband, Richard John Bingham, the 7th Earl of Lucan, known as Lucky Luke, or Bluey. A peer of the realm was convicted of bludgeoning their nanny Sandra Rivett to death with lead piping in their Belgravia house and nearly succeeding in murdering his estranged wife before he fled, disappearing without trace. It seemed like the plot of an Agatha Christie novel. Veronica described the attack in her autobiography I was helping her to write. “I screamed and my husband said, ‘Shut up!’ and thrust three gloved fingers down my throat.” He did this to muffle her cries from their three children upstairs, one in Veronica’s bed watching the Six Million Dollar Man. She described the terror she endured. “We started to fight. He attempted to strangle me from in front and gouge out my eye. I gasped, ‘Please don’t kill me, John’.”

Speculation over Lord Lucan’s disappearance continues to hold the nation’s attention even though all the major players are now dead. Lord Lucan was the first member of the House of Lords to be named a murderer since 1760. He was also the last person to be committed by a coroner to a Crown Court for unlawful killing. Despite the way her family turned on her for giving her testimony, it was not Veronica’s evidence that convicted Lord Lucan, there was quite enough evidence without that and, as his wife, she was not permitted to give testimony about the murder of Sandra Rivett.

Early on in our friendship Veronica had confided that had her husband not murdered Sandra Rivett, “I certainly would not have reported his attempt on my life.” Nevertheless, her own family and his blamed her for the downfall of Lucky Luke. After the court case and the manhunt for Lord Lucan, the rest of the world moved on, leaving Veronica trapped in a lonely odyssey, financially bankrupt and starved of any friendship, compassion or empathy, hunted by frenzied media speculators and haunted by the guilt she felt for the death of Sandra Rivett. At the time Veronica was only 37 and still beautiful. She may have found love again had she not been cast into the Kafkaesque nightmare from which there was no escape.

Veronica felt dehumanised by what she considered ghoulish curiosity and the continuous humiliating attempts to discredit her account of events. Conversely, Lucky Lucan lost none of his shine. He remained a god – albeit a toppled god – the embodiment of 007, for Lord Lucan was the man Ian Fleming had been so determined would play James Bond. Veronica firmly believed that, following his failure to murder her, Lord Lucan had, in her words, “bravely thrown himself into the propellers of a ferry the night he disappeared”.

She told me: “His knowledge of propellers was extensive so he would have been confident that no remains of his body would be found, thereby he could not be declared dead and his family could ensure I would lose custody of our children.” If true, it was an act of wickedness.

So much of the pathos of her life was rooted in her own sense of honour. Only after the parents of Sandra Rivett had died and her husband had been pronounced dead did Veronica feel free to tell the truth of the events leading up to and following her husband’s murderous attack and disappearance, and the true horror of the unfolding nightmare she endured afterwards.

WHEN NEWS reached me last year that Veronica had died, I was felled with grief. It was like losing my own mother – also called Veronica – all over again. For Veronica Lucan had inspired me through my own struggle with a brain tumour. Her optimistic pragmatism did not leave room for fear or doubt. Bringing up young children in Mayfair, visiting St James’s Park to watch the feeding of the pelicans was a daily part of my life and it was there I first met Veronica in the early 90s. She’d often persuade my sons or other children not to let a duck build a nest in a spot they’d be sure to be disturbed.

In these last few years I’d been helping Veronica write her autobiography and wept at the prodigious list of mind-altering drugs she had been force fed by unscrupulous doctors after her husband’s trial. Her clean bill of mental health, which she’d received after a voluntary stay at The Priory in 1973 when Lord Lucan was attempting to have her declared insane, was no protection from unscrupulous doctors. Thousands of sane women like Veronica were force fed cocktails of drugs in the 70s and 80s which evoked paranoia and hallucinations. The hair-raising story of how she escaped the mental asylum where she had been forcibly placed and made her way to her own doctor who gave her protection and assisted her to wean herself off the drugs is a movie in itself.

Veronica often told me the media frenzy surrounding the nightmare of that ghastly night in November 1974 left her feeling utterly dehumanised yet she was essentially a positive, dynamic woman and her determination shone so brightly, it seemed impossible that it could ever be extinguished. Chatting with her over a cup of tea, I would frequently realise she was oblivious to a social meme and I’d be reminded that she had spent over 40 years living in seclusion without a television. And she had an enormous presence for such a little lady. As one of London’s true eccentrics, her unshakable sense of fun, mischief, vitality and humour persisted, even in her darkest hours. Her wit was wry and at times arch but there was a girlish gaiety about her that sparkled. With her long grey-white hair drawn up in a glamorous updo, her pale skin and graceful precise movements, she was reminiscent of a tiny medieval queen, a vision from another age, preserved in aspic.

When my brain tumour made living in my fourth-floor home on Mount Street in Mayfair impossible, I moved into my club in St James’s. It backed onto Green Park and Veronica became a frequent visitor, dropping by after watching the daily feeding of the pelicans. We would sit in the drawing room, sipping Earl Grey tea overlooking the park and talk the way women talk about everything and nothing. Most of all we laughed. Veronica was terrifically funny and though she could be waspish it was usually at the expense of some chap puffed up by his own self-importance.

Veronica did not live in the past except in that she remained true to the values of her generation. The grace with which she endured her lot made her utterly captivating. Truth was a matter of integrity and however awkward or uncomfortable it was, she did not flinch from speaking it. My precious, sweet funny kind-hearted friend was a vibrant active women as comfortable dining among the art crowd of Groucho’s in Soho as she was taking tea at the Goring Hotel. In understanding the mischievous wit and graceful stoicism of Veronica – for she never used her title – it is important to remember she was shaped by a generation that saw respect as something one had for oneself, not something to be demanded from others; a generation that valued humility above pride and for whom truth was an absolute and not as she would remark “a point of view”. She had no patience for self-indulgent introspection. Veronica always described herself as a “matter-of-fact woman and John as a matter-of-fact chap”, I think she meant by this that she was accepting of whatever life threw at her and unwilling to make a fuss. I remember at a dinner at the Groucho last year when Veronica and I were discussing our marriages and our lives and when we decided our lives might have been better had we made more of a fuss. However, her ability to maintain her equanimity served her well in the early years of her marriage to a professional gambler.

Veronica was part of Mayfair’s Berkeley Square Set in the 60s and 70s, a glamorous world in which John Aspinall recreated the rituals and atmosphere of aristocratic refinement and gentility. I remember walking through Berkeley Square with my spaniel at night awed by the queues of gentlemen in black tie and ladies in tiaras and ball gowns, alighting from Rolls Royces and Aston Martins. I’d watch them give keys to the valet waiting outside Annabel’s where they’d dine before going upstairs to the chandeliered magnificence of the Clermont Club. This world of opulence and grandeur was peopled by aristocratic women, gliding along in sable stoles on the arms of powerful men, idly tossing family fortunes on the roulette wheel. Women draped in diamonds, elegantly smoking cocktail cigarettes from telescopic cigarette holders as they observed the sacred ritual of the passing of the chemmy slipper during a game of baccarat in which the fees for Eton would be won or lost. Notwithstanding the 43 years which has passed since the fateful night in 1974, I often caught glimpses of the woman she was then, before her world imploded.

VERONICA was born in Bournemouth in 1937 to Major Charles Moorhouse Duncan and his wife Thelma. Her father died in a car accident while she was young and, after a short time living in South Africa, the family returned to England. Her mother then married the manager of a hotel in Guildford and Veronica and her younger sister, Christina, attended St Swithen’s, a boarding school in Winchester with a reputation as an academic ‘hothouse’ and a ‘blue-stocking’ breeding ground. With her talent for art, she went on to art school in Bournemouth and always regretted not pursuing art as a career, instead she fell into modelling while sharing a flat with her sister on Wilton Crescent. Her sister later married William Shand Kidd, the step brother of Peter Shand Kidd who had married Princess Diana’s mother in 1969 after her divorce from Princess Diana’s father John Spencer, the Earl of Althorp.

She first met her husband while visiting her sister Christina and husband. She’d been told beforehand who he was and knew he was Eton-educated and had been in the Coldstream Guards. Veronica was not obsessed with class and John – whose parents were socialists and rather peculiar – soon bonded over their shared view that the Shand Kidds were social climbers. Observing her husband for the first time, she described him as, “looking like a gentleman almost in caricature… with baggy cavalry twills and tweed cap to his height and moustache on his youthful face.” For their first date he took her to Annabel’s on Berkeley Square which had only opened that week – he was a founder member – picking her up in his “run-around, a Grey Simca”.

Soon after dinner, John took her to Cowes where he had a power boat and their courtship began. He taught her backgammon and asked about her own work. He explained he was a professional gambler and took pains to give her a clear idea of what being married to such a person might mean. They married in 1963 at a wedding which was “sparsely attended because neither of us was very popular”. They took the Orient Express to Istanbul but even that was a disaster as there was no food carriage and they lacked the local currency to buy anything to eat along the way. They flew home after one night in Istanbul.

A year later, Lord Lucan inherited his father’s title, becoming the 7th Earl of Lucan. As the wife of a professional gambler her financial situation was always precarious and she became accustomed to pretence. Everything about her lifestyle as a countess looked terribly grand on the surface. She had endless credit on Savile Row and an account at Harrods but she was forever anxious as to how they’d find the money for the electricity, water and gas bills. By the time Lord Lucan disappeared in 1974 he had five enormous overdrafts at five different banks and pockets full of IOUs. She explained to me that part of her role as a gambler’s wife which she found especially trying was staging hysterical scenes in order to extricate her husband from a game in which he was losing badly, or to escape the “gentlemanly game” in which, after a big win, a gentleman would give the losers a chance to claw back some of their losses. Their life was entirely entrenched in gambling and the Clermont Club and their relationship followed a flowchart of his winnings and losses. She explained that their conversation was “on a limited plane”. When he walked in through the door she’d ask, “What happened?” Reply, ‘I lorst.’ However, if he said, ‘I broke even.’ I was happy.” She explained that “when we were having a good run I was able to enjoy spending money. I bought myself clothes and things for the house. My husband bought me jewellery.”

He was backed by the club so half of his winnings went to Aspinall who funded much of his gambling. In their own aristocratic way, Lord and Lady Lucan were a “Bonny and Clyde” act, but it was an act which painted Veronica in a mentally unstable light. She found the charade especially galling given her pride in her even-tempered equanimity, as these staged scenes tarnished Veronica as a hysteric with John as the long-suffering husband.

Of all her misfortunes, it was her children’s rejection of her that ultimately broke her heart and made it impossible to move on. When we spoke about our children, we spoke of the things mothers speak of, our hopes and fears and disappointments and we shared our concern that perhaps we weren’t naturally maternal which I think nearly all mothers fear deep down though few admit. Veronica was an absurdly proud mother and took enormous pride in her children, even after their estrangement. She always described the birth of George as bringing “more joy to me than any single event in my life”. Lord Lucan wasn’t at the birth but playing bridge with a mutual friend of mine, Selim Zilka. They were in his flat which was near mine in Mayfair and Selim later told me that – “in a rare display of joie de vivre for John” – upon hearing of the birth of his son, “he jumped up in the middle of a rubber and danced about” before sitting down and finishing the game.

I can only imagine the devastation she must have felt upon receiving the letter her then 15-year-old son George wrote from Eton in 1982 that henceforth it would be more “congenial” for him (and his two sisters) to live with her sister, Christina and brother-in-law, William Shand Kidd rather than their own mother. Her brother-in-law’s step brother, Peter Shand Kidd was at that time married to Francis, Princess Diana’s mother. Prince William had just been born and Veronica nobly accepted their decision. Veronica didn’t want to traumatise them or divide her children’s loyalties nor subject them to a court case so she bowed out gracefully but it wounded her deeply and added to her sense that she wasn’t good enough.

I remember her giddy with excitement when George and his wife wrote requesting a meeting. She prepared a grand tea and sat waiting for them dressed in her best suit in her drawing room while they waited in the Goring Hotel. The very idea of such an intimate rapprochement with her beloved son in such a public setting, which would inevitably be picked up by the media, horrified Veronica. She had yearned for this day, prepared for it, planned for it; carefully preserving all of his father’s personal possessions for her son, from Savile Row suits to golf clubs. All these were lovingly awaiting his visit in the childlike fear that she herself might not be enough. It was heart-breaking.

Just before her death, Veronica was betrayed by yet another unscrupulous man with whom she’d struck up a platonic friendship. He had asked for access to her storage unit and made off with Lord Lucan’s Savile Row suits of which her husband had been inordinately proud. Ironically it was Veronica’s sense of decency and honour which was the cause of so much of her pain, for it ensured she never wavered in her rectitude despite the ruinous cost to her own happiness.

Tyne O’Connell is an author and Mayfair historian