The allure of high-complication hand-crafted timepieces simply can’t be beaten – and yes, they’ll even outlive the Apple Watch too. Hazel Plush reveals why.

In an idyllic Swiss village not far from the Rhone River, there’s a small miracle in progress. Dressed in white coats, hovering over microscopes, and sealed from the outside world in their airlocked laboratory, this team of men and women look like scientists at first glance – but they’re engineers, artists, craftsmen, gemologists. Working to miniscule scales, they are creating some of the finest, most complicated watches on earth – timepieces that will fetch hundreds of thousands of pounds, maybe more. They’re the masters of watchmaking; creating the next generation of chronographs – miraculous, yes, but the real wonder is that they’re here at all. Because, if common sense had prevailed, their work would be obsolete.

Ask any horologist who invented the first mechanical watch, and you’ll never get a straight answer: The history books are muddied with conjecture, but one thing remains certain: The 1770s were landmark years for the craft. Hitherto, portable timepieces – hand-wound, and powered by a mainspring – had been heavy, temperamental, inexact. If you wanted precision, you were better off with a pendulum clock. But a small band of talented engineers were making strides.

Swiss-born Abraham-Louis Perrelet led the effort, inventing in 1777 the self-winding mechanism – powered by the movement of the watch wearer, rather than a hand-wound spring. “Just 15 minutes of movement is needed to power it for eight days,” claimed a report by the Société des Arts in Geneva. Revolution indeed. Other watchmakers, including Hubert Sarton and Abraham-Louis Breguet, forged ahead with their own designs – and development of the self-winding mechanism spread through Europe. It wasn’t perfect, but it was progress.

Over the next 125 years, portable timepieces became the hallmark of the elite. Men favoured pocket watches, while wristwatches were more fashionable for women – marketed as bracelets, and often adorned with diamonds, precious gems, and intricate hand-painted designs. However, few new patents were filed during this time: Watches grew in opulence, but not in accuracy.

But a watershed moment came in 1904, after Brazilian aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont complained to Louis Cartier that it was tricky to check his pocket watch while airborne: He needed both hands for flying. Cartier created a practical, flat, wrist worn design with a leather strap – the “Santos de Cartier” – and the pilot watch was born.

Changing fashions

During the First World War, the idea really caught on. Service wristwatches were issued, designed to withstand trench warfare with their reinforced glass faces and luminous dials. Military pilots relied on their timepieces just as Santos-Dumont had, with extended leather straps to fit over their flying jackets. In 1917, the Horological Journal reported that “the wristlet watch was little used by the sterner sex before the war, but now is seen on the wrist of nearly every man in uniform and of many men in civilian attire”. Fashions were changing, and the Second World War brought an even more pressing need for accurate, durable designs: A far cry from the frivolous diamond-clad wristwatches of the 1800s.

Innovation boomed. The village of Plan-les-Ouates, near Geneva, had become a hub for high-end watchmakers: The likes of Rolex, Vacheron Constantin and Piaget developed workshops there, and the post-war years saw them busier than ever.

Not content with merely keeping the most accurate time, watchmakers turned their attentions to more specialised functions, or “complications”. They included “perpetual calendars” to keep track of the date, “minute repeaters” to chime the time, altimeters, lunar calendars and auxiliary dials – to name but a few. The “tourbillon”, a mechanism to improve the timekeeping accuracy, was perhaps the most prestigious advancement – only available in the most expensive of watches.

Some watches were powered by the new generation of self-winding mechanisms; others were simply still cranked by hand.

Everything changes

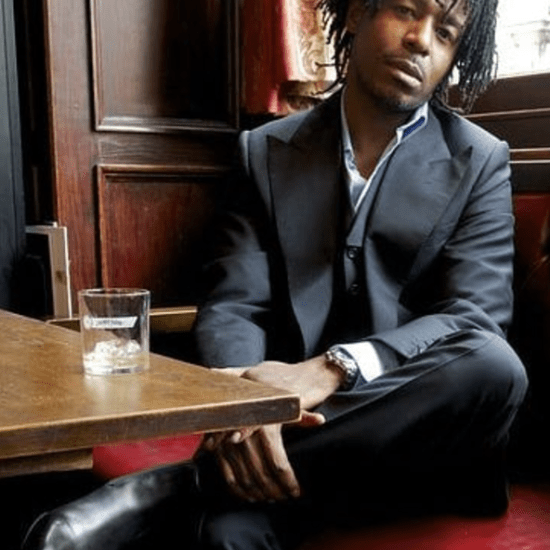

The watch became, once again, a symbol of status and wealth, marketed to buyers all over the world with celebrity endorsements and sponsorships galore. Steve McQueen sported the TAG Heuer Monaco, while Paul Newman chose the Rolex Daytona. Elvis wore a Hamilton Ventura, while Miles Davis wore a Breitling Navitimer. Watches were a fashion statement, too: Andy Warhol was rarely without his 18ct gold Cartier Tank. But then came quartz – and everything changed.

Receiving power from a battery, with hands controlled by a circuit board rather than a mainspring, wristwatches had never been more accurate or lightweight. Analogue quartz watches were first toted at Geneva’s Baselworld watch fair in the early 1970s – but it was their digital counterparts (with LCD faces and no moving parts) that really caused a stir. Quartz timepieces, quickly became the new status symbol: Why rely on ancient craftsmanship, when you could wear the future on your wrist?

In the 1970s, there had been over 1,600 watchmakers in Switzerland; by the mid-1980s, there were fewer than 600. The end was surely nigh for Europe’s luxury timepieces.

Rolex and Blancpain persevered with hand-crafted movements – the latter spurning quartz completely. In 1980, Patek Philippe began designing a new exclusively mechanical pocket watch to mark its 150th anniversary in 1989 – though nobody was sure if it would ever make production.

Gradually, auction houses noted a slight trend for vintage mechanical watches. Now that they were almost obsolete, they’d become a nostalgic indulgence – and perhaps their impending rarity might increase their value?

By the mid-1980s, the prestige, rarity and craftsmanship of high-end mechanicals had weathered the quartz crisis.

Patek Philippe’s anniversary Calibre 89 – completed, finally, in 1989 – sold at auction for $3.1 million. In spring 1990, Swiss watch exports totaled $1.5 billion.

The rest is history. In Geneva, where the world’s finest watchmakers showcase their new designs, to see that the market for high-calibre, highly complicated timepieces is more buoyant than ever – even with the rise of wrist-worn computers, such as the Apple Watch.

Yes, based on their primary function, mechanical watches are obsolete. We no longer need them to tell us the time. But we do want them: To remind us of the power of the human brain and hands, perhaps, or

the joy of an exquisitely-engineered movement. The mass-production line is, quite simply, no match for handcrafted perfection: Some things really do stand the test of time.