|

MASTER CHEMISIER IN LOVE WITH SHIRTS

Frank Foster loves what he does: He loves making shirts, he loves buying textiles and he loves meeting people, all of which he has been doing for more years than he might care to say from an Aladdin’s Cave of seeming chaos opposite the RAC club.

Here, in a warren of small rooms he creates shirts for  the rich and famous from around the world and for those who are just plain discerning. the rich and famous from around the world and for those who are just plain discerning.

“I love making shirts,” he says. “Retire? No, I'm not retiring.”

He started life as an artist, training at the Central School of Art, and somewhere along the way had a bout as a boxer, as well as “the enjoyment of wine, women and song”. There were exhibitions of his paintings in various London galleries.

Then his talent for hand blocked printing lead him start printing exclusive silk  head squares that were taken up by royalty. Buyers began asking for silk shirts and around 1958 he launched his career as a master chemisier. head squares that were taken up by royalty. Buyers began asking for silk shirts and around 1958 he launched his career as a master chemisier.

“I didn’t have any training. I unripped some good ones and looked at the structure. As an artist, I understand structure. I then taught myself to make and cut the patterns.”

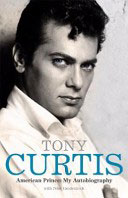

That he was successful may be judged by his roll call of customers that ranges from such glamorous film stars as Errol Flynn, Ray Milland, Cary Grant and Tony Curtis through to designers Hardy Amies and Hartnell, mafiosa, other celebrities, captains of industry and royal figures today.

Every picture may tell a story but it can't tell how soft is the make of Foster's shirts, nor the softness of the packed shirt, above. This has no pins to hold it in place.

Below, just some of his famous customers, Peter O'Toole in Foster's robes in Lawrence of Arabia, Steven Spielberg and Tony Curtis, who died recently.

“I forged strong links with the theatrical world, with Bermans, who used to be the top theatrical costumiers. I’ve made for all sorts of films. I made the shirts for “My Fair Lady” and the robes for “Lawrence of Arabia”. I’ve just  sent material samples to Steven Spielberg for two films. I don’t make shirts for films now, it is just too much work, but they still come to me for textiles.” sent material samples to Steven Spielberg for two films. I don’t make shirts for films now, it is just too much work, but they still come to me for textiles.”

Textiles are his passion. He buys from Italy, South America, Austria, France, the US, Switzerland – from wherever there are interesting designs and beautiful fabrics, salesmen bringing the finest of cottons, silks, linens, wools and cashmeres, knowing that he loves the very  best. “I can’t resist them,” he says. best. “I can’t resist them,” he says.

He pulls a pure wool taffeta from the stack of rolls. “This was made on a silk loom, isn’t it wonderful? They don’t make it any more. Too expensive.”

Finest cashmere from Scotland makes up into luxury casual shirts. Heavier weights are used for dressing robes and blanket throws. The stock overflows throughout the tiny workshop, crowding in upon his desk, surrounding the sewing table. “Some of these cloths go back over a 100 years.” They are exclusives, one-offs, a treasure trove of textiles.

He is a mine of anecdotes about the famous. “I shared a flat  once with Norman Widsom. I made his shirts. Everything he wore was bespoke made – shirts, suits shoes. And then everything was subjected to washing and friction, so that the shirts shrank, and the suits too, and the shoes were pulverized, all of which helped to make him look funny.” once with Norman Widsom. I made his shirts. Everything he wore was bespoke made – shirts, suits shoes. And then everything was subjected to washing and friction, so that the shirts shrank, and the suits too, and the shoes were pulverized, all of which helped to make him look funny.”

Another customer, the great Orson Welles arrived at the Savoy hotel and sent for him to come over. “I’ve never been,” he hesitates slightly, “subservient. I sent back that it was the same distance from there to me. He didn’t come. But it didn’t matter,” he smiles.

Cary Grant called in once, needing urgent repairs to his trouser fly. “I told him to take his trousers off and wait while the girls did it. So he sat in my office, in a pair of see-through underpants with frills, and had a cup of tea.”

He cuts all the patterns and does the fittings, makes any alterations necessary. “Most shirtmakers now don’t do fittings but I do.” He is helped by his wife Mary,  and a couple of part-time workers. and a couple of part-time workers.

The make is soft, supple. Various details may be added – pleats, fancy work, extra buttons, contrast linings inside collars and cuffs.

"There is nothing new in shirt styles. Its all in the detail. Ready-made shirts pleat their sleeves into the cuffs, ours are gathered in. There's a button on the gauntlet. We may curve the cuffs, which is difficult for ready-mades, so that there aren't points to fray. I designed the cocktail cuff, a double cuff that fastens with buttons.

“I once made shirts for J. B Priestley, who wanted detachable cuffs. I made them with buttoning all round so that they could be taken off when he was writing.

“People are pests, you know. They come in here having seen something in a magazine, these old boys with big bellies, looking for fashion. There is no such thing as fashion.

“I give customers a pair of scissors and tell them  to look around and find the shirtings they like. They cut off small samples, which are attached to the order page in this book,” (no computer nonsense here) “and we discuss what they might want. It will be 8 to 10 weeks before the shirts are ready.” to look around and find the shirtings they like. They cut off small samples, which are attached to the order page in this book,” (no computer nonsense here) “and we discuss what they might want. It will be 8 to 10 weeks before the shirts are ready.”

Above, soft formal shirt with initials on the pocket and a button on the gauntlet. Right, just some of the profusion of textiles in Foster's workrooms.

The place may seem chaotic but the results reveal the love of the craftsman for his work. Foster handles each shirt with appreciation, fondles the fabric, remembers where it came from. He too is a treasure, one of that small band of people who combine creative talent with dedicated application.

Some customers say he should put his prices up, that they are too modest by today’s standards. “But why would I want to do that?” he asks. “I love making shirts.”

|