SCENT & SENSIBILITY

Seven doyens of Savile Row, renowned for their sense of touch, tell us what their favourite men’s fragrances are…

Alexander Lewis, Norton & Sons

I have a very strong nose and it’s something I think carefully about. I wouldn’t go so far to say I’m a “nose” but I am very attuned to smells. I wear Lumière Blanche from Olfactive Studio, which works with different photographers. This particular one was a collaboration with Massimo Vitali. The top notes include cardamom and cinnamon with heart notes of almond milk and cashmere wood, with base notes of cedarwood, sandalwood and Tonka bean. I’ve been wearing it for a year and a half. I mix it with other fragrances such as a new fragrance from Diptyque and Escentric Molecules 01. I spray one on top of the other.

www.olfactivestudio.com

____

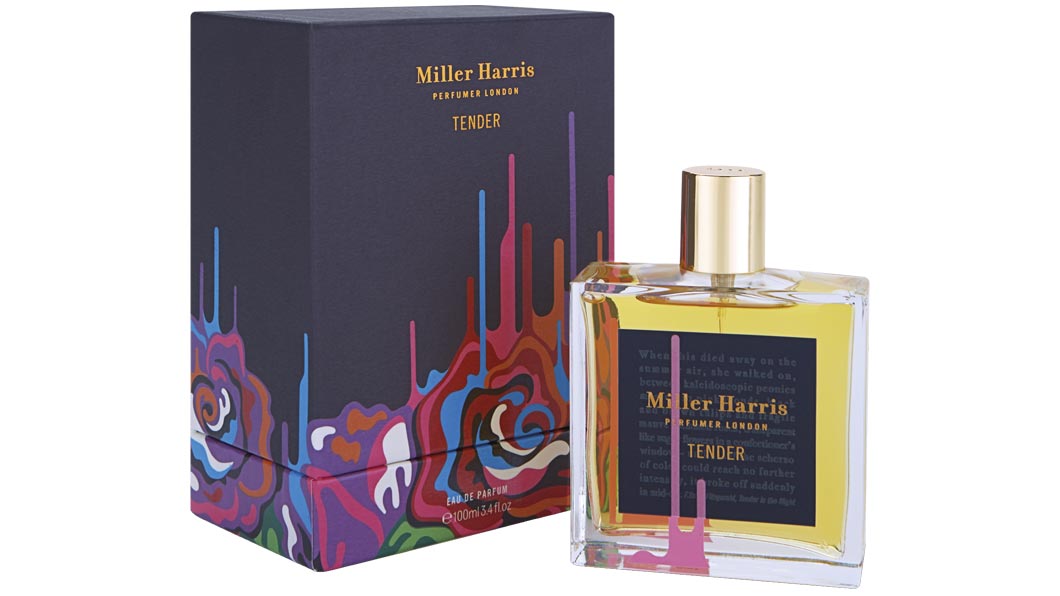

Kathryn Sargent, Kathryn Sargent

Tender by Miller Harris is my favourite male fragrance because of how unique it is; it is light, floral and leathery paired with the interesting note of ink which creates a really interesting and sophisticated smell. Harris created this fragrance in response to Tender is the Night by F Scott Fitzgerald. One of my first clients introduced me to the scent and it often brings back memories of when I first set up my tailoring company.

www.millerharris.com

____

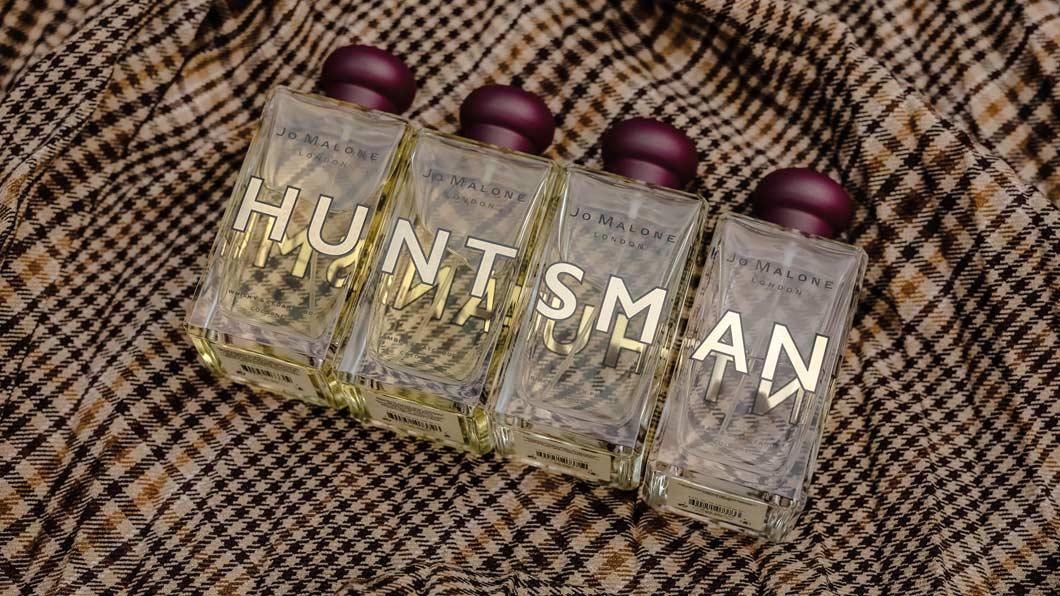

Campbell Carey, Huntsman

I travel often for trunk shows, so when in warmer climates I wear the Assam and Grapefruit scent from Huntsman’s Jo Malone collection. Whilst away, I prefer my fragrance to be light and invigorating. This scent is incredibly fresh with notes of maté and patchouli, so it’s the perfect summer or holiday fragrance.

I’m currently wearing the Whisky and Cedarwood scent by Huntsman and Jo Malone. I love the dark, spicy notes of whiskey paired with the warm, wintery scent of cedarwood – they complement each other perfectly. It’s a great fragrance for the changing seasons – it makes me very excited for the wood burning fire to be lit at Huntsman.

www.huntsmansavilerow.com

____

Simon Glendenning, Dugdale Bros

When it comes to my favourite cologne, I always opt for one that complements the season. That’s why in the autumn and winter months, you’ll find me reaching for a scent I’ve used for over 20 years, Czech & Speake’s bergamot-inspired No. 88. The invigorating smell of vetiver and sandalwood makes it rich, masculine and for some reason redolent of Christmas – all at the same time. However, in the spring and summer seasons, I prefer to use Creed’s Original Vetiver – my wife once bought me this as a birthday gift, and its light and earthy aroma of musk and mandarin has made it a favourite ever since.

www.czechandspeake.com

____

Dominic Sebag-Montefiore, Edward Sexton

I came across French Leather fairly recently. The brand was introduced to me by a client who’s a connoisseur and I wanted something that was disconnected and I really like Santal by Le Labo but I do find it a little bit everywhere. I wanted something a bit different. I went into Les Senteurs in Elizabeth street and they introduced me to French Leather. Previously I’ve worn vetiver and patchouli but I find vetiver a bit grassy and I find patchouli a bit strong but they’re in there with frankincense and juniper. I wanted something a bit heavy, a bit deep for winter, but the vetiver lifts it and it’s lovely and complex but still lasts beautifully. It’s a lovely scent.

www.lessenteurs.com

____

Simon Cundey, Henry Poole

Acqua di Parma is my chosen aftershave. I’ve been wearing it since 2001. Before that I used to wear brands like Eau Sauvage and Ralph Lauren Polo. What I especially like about it is the Bakelite top. I thought the freshness of it was incredible and gives life to it. Some fragrances are very heavy and musty and overpowering sometimes. Others are sweet and almost sickly. But this is timeless – you don’t get tired of Acqua di Parma.

www.acquadiparma.com

____

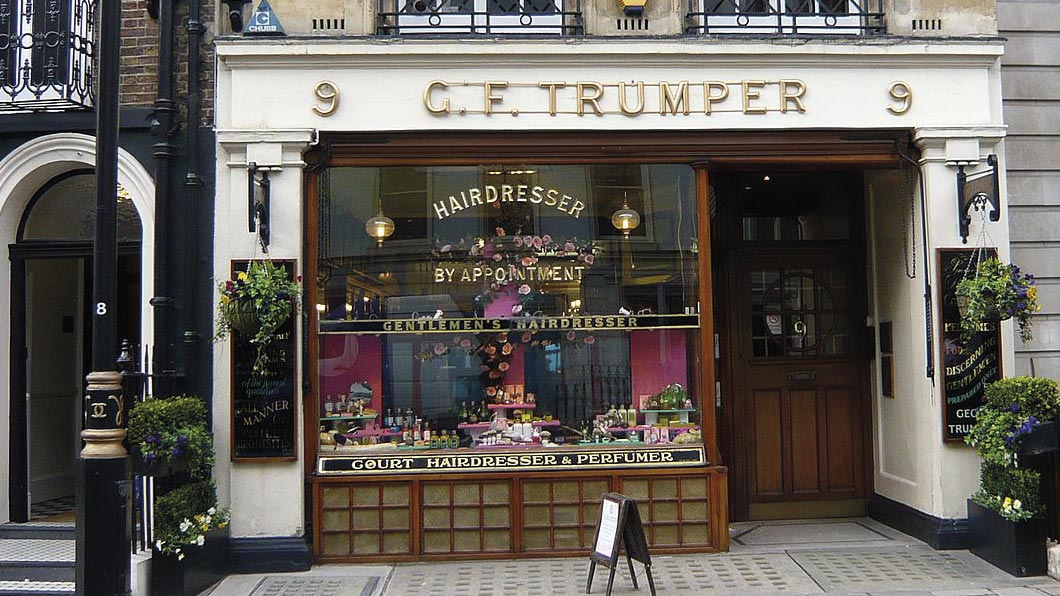

Geoff Wheeler, Huddersfield Fine Worsteds

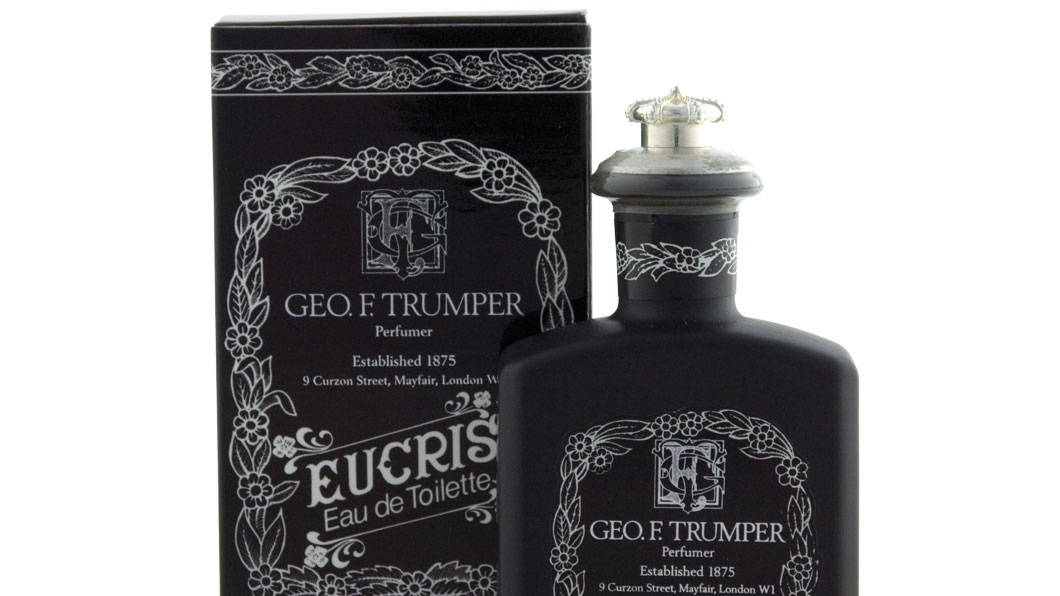

I wear Eucris by Geo F Trumper. It has a very old school class about it. It’s not fragrant, it’s almost musty. I first came across it mentioned in the James Bond novel Diamonds Are Forever, and I thought, if it’s good enough for 007, it’s good enough for me.

The most annoying thing about it is its cap, which must have been designed when it was first invented. I can’t tell you the number of times it’s nearly gone down the plughole.

www.trumpers.com

____

Seven doyens of Savile Row, renowned for